Systems and Strategies - TB871 Block 1 (Tools)

Block 1 Overview

"How can systems practitioners converse systemically with situations of complexity and uncertainty to make strategy?"

- TB871 (Reynolds et al., 2020)

Having completed The Open University TB872 module 'Managing Change with Systems Thinking in Practice (STiP)', I begin TB871 'Making Strategy with STiP'. Where TB872 was more focused on situated praxis and second-order change using tools such as PFMS and BECM, TB871 is more focused on evaluating and adapting systems tools to complex and uncertain situations. This shift addresses the difference in systems approaches that bring attention either to the practitioner or the situation of interest as a point of praxis. However, both modules emphasise reflective practice situated in real world contexts, using an epistemological constructivist approach (systems as conceptual constructs for learning) rather than positivist (systems as representations of the world).

One of the primary conceptual constructs for learning that we are introduced to is the 'STiP heuristic' which guides learning and provides methodological framing for making strategy with STiP. The phrasing of 'making strategy' appears to be an intentional choice, probably in avoidance of meanings associated with the term 'strategising' used in organisational settings, conveying different types of practices. This is similar to the avoidance of the term 'management' in regards to managing change with STiP in TB872—the term is often used in regard to more systematic ways of working which systems thinkers would say is just one part of 'managing'.

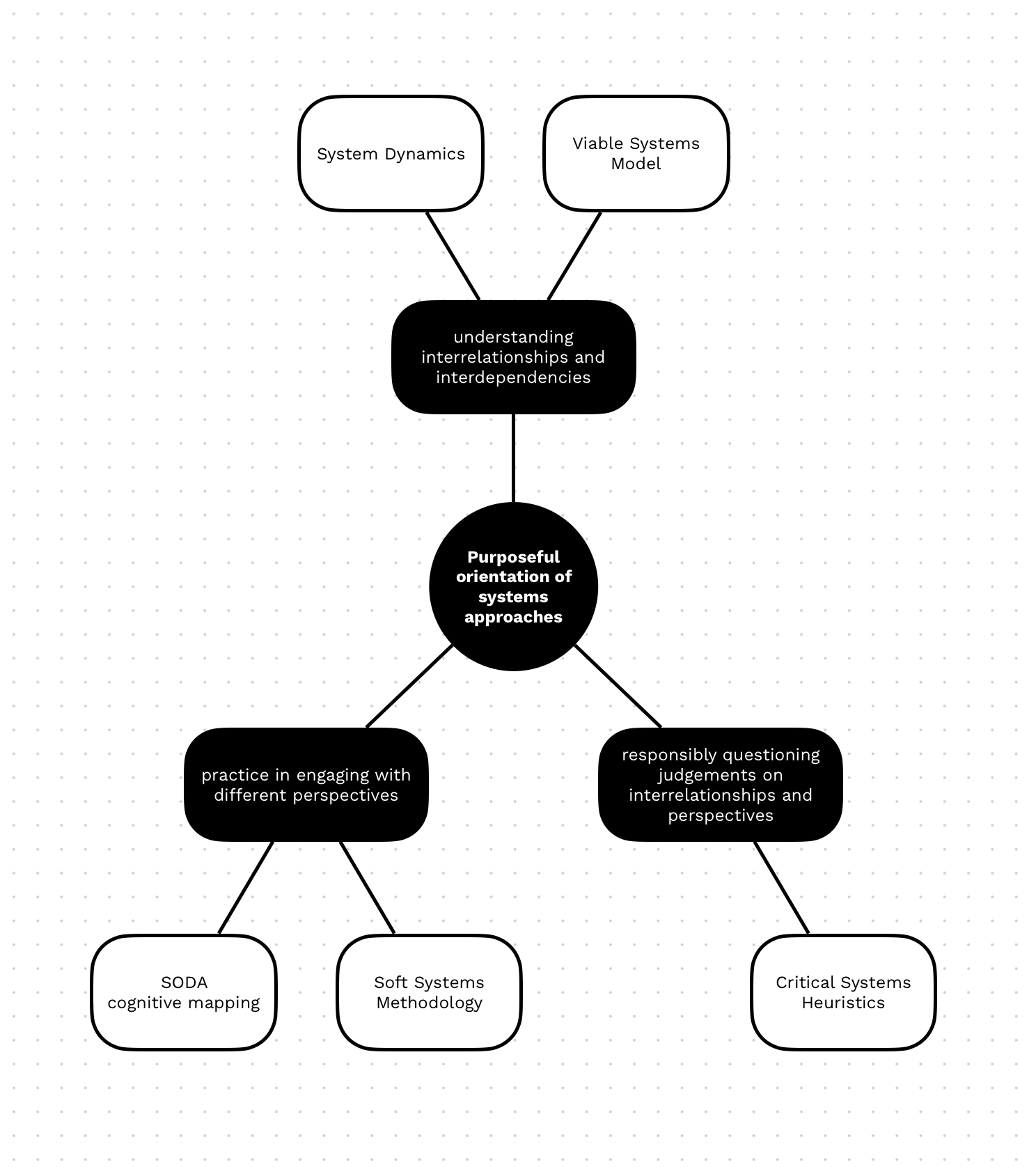

For TB871, I will need to choose an Area of Practice (AoP) which is a high level domain, role or area of responsibility within which there may be potential for identifying 'situations of interest' that can benefit from intervention and strategic thinking. A 'system of interest' can be constructed to explore and analyse aspects of the situation of interest. The STiP heuristic helps to reflect on the inter-related elements of perceived reality requiring transformation by prompting action towards:

understanding interrelationships (uIR)

engaging with multiple perspectives (eMP)

reflecting on boundary judgements (rBJ)

Within the context of my AoP, I will utilise specific systems tools in five different blocks of the module. Each block also has a 'People stream' that should help with exploring contextualisation of approaches to human behaviour in a variety of contexts. As in TB872, I am sure we will be encouraged to engage in reflexive practice, questioning the nature of knowing and how that affects our use of tools and ideas for making strategy.

To begin with, I review the primary areas of focus in this course of study, and reflect on some of the issues that are helped by strategic systems thinking.

Orientations of five strategic systems approaches

What are systems?

The Open University definition, as referred to by Morris (2003), states that a system is:

a collection of entities...

that are seen by someone...

as interacting together...

to do something.

Based on this definition, I consider what kinds of items would be described as a system. Here are some examples:

A health centre

YES: There are multiple entities working together purposefully to provide health care—it is designed as a system.

Poverty

NO: This can be seen as a function or outcome of a system. However, the process or experience of being in poverty can be seen as a system, as there are various factors at play to create the circumstances for poverty and it can be seen as having its own specific outcomes as a result of those factors interacting.

A garbage bin

MAYBE: The biological and chemical processes in the bin may be considered to be of importance to the observer; even if they are not conscious of this perception, they may be aware of the effect of interacting with the bin unhygienically thus forming a system in which lifeforms are affecting each other.

Washing dishes

MAYBE: This is a process in which various elements interact, resulting in an outcome. It is not usually seen as a system because of its ubiquity but it can be visualised, designed and evaluated as a 'system to result in clean dishes/kitchen' for example.

A local council

YES: There are multiple entities working together purposefully to provide health care—it is designed as a system.

In any case, the human perspective is necessary to determine what is considered a collection of entities, whether those entities are interacting and achieving something. The human determines what the purpose/function of the system is, and decides if the subjects are fulfilling that purpose/function.

Perspectives on systems approaches

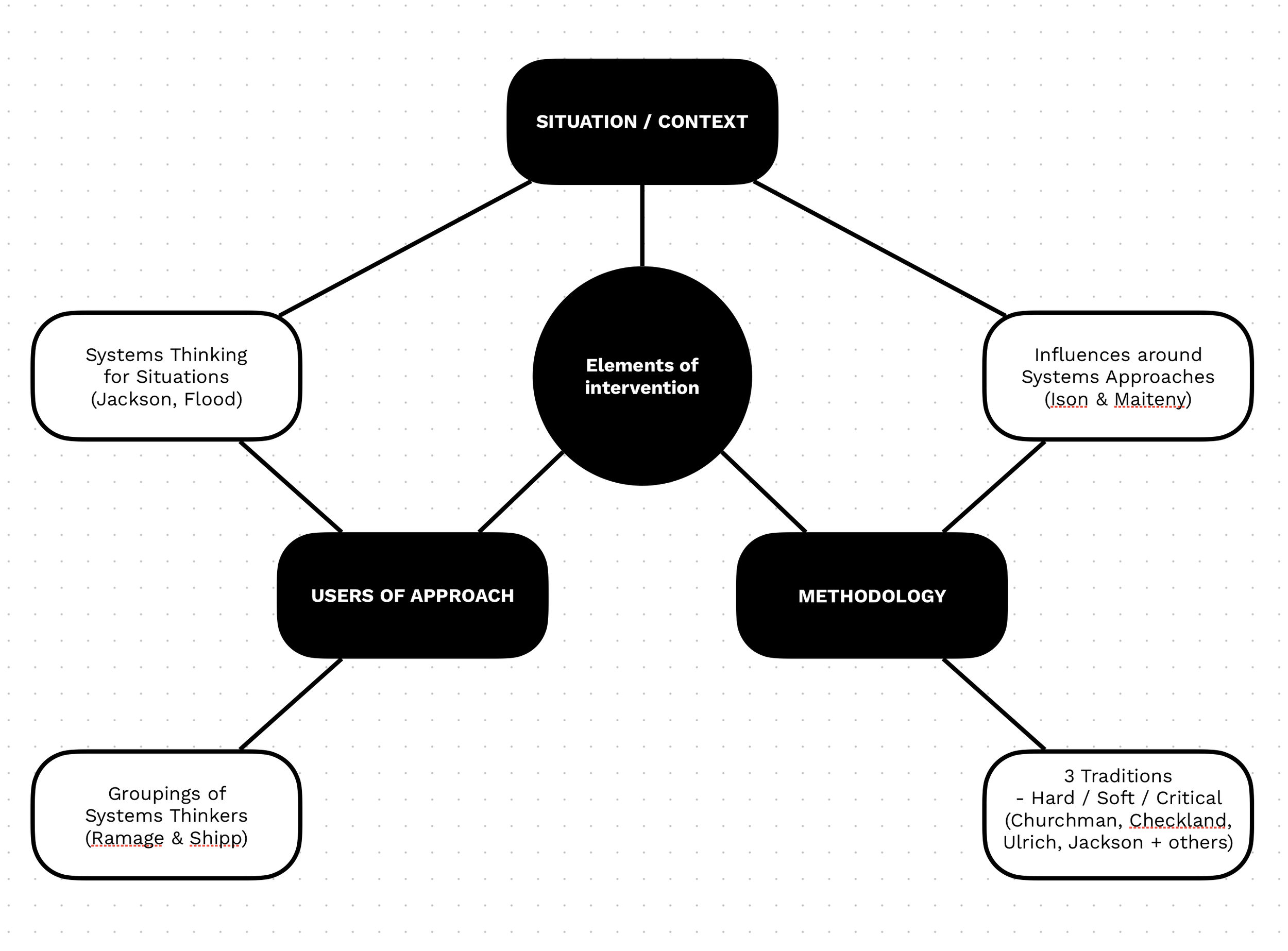

There are several perspectives on systems approaches that put varying levels of emphasis on the systems thinking practitioner, and the situation in which the approach is used:

| Perspectives on systems approaches | Relative emphasis given to… Situation of use | Relative emphasis given to… Systems thinking practitioner |

|---|---|---|

| Perspective 1: ×3 traditions hard/soft/critical | Emphasis on categorising approaches based on the situations in which they are used | Makes selection of approach easier in some ways, as they are categorised in a simplistic way |

| Perspective 2: Total systems intervention (TSI) | Provides a framework for exploring problematic situations, choosing and appropriate approach, and implementing it | Does not consider different perspectives on how categorisation of approaches or utility in various situations |

| Perspective 3: Influences on systems approaches | Encourages use of wider influences including approaches and situations of interest (different perspectives on the situation) | Acknowledges influence of practitioners on use of approaches |

| Perspective 4: Groupings of practitioners | Limited reference to specific use cases | Bringing focus to the lives of practitioners highlights the influences on their thinking |

Elements of intervention in systems, from different perspectives on systems approaches

The different perspectives on systems approaches utilise different strategies for analysing and managing systems change.

Situation-focus (variables)

- how each approach assumes the external world to be, ranging from being comprehensible and controllable to being unpredictable and confusing, with a focus on situations:

the substance of strategy is complex

strategy involves issues of both content and process

strategies exist on different levels

(Mintzberg et al., 1998 (TB871 1.2.4), using ideas from E.E. Chaffee)

Schools of making strategy (descriptive):

the learning school, which sees strategy as an emergent process – strategies emerge as people come to learn about a situation as well as their organisation’s capability of dealing with it

the power school, which views strategy emerging out of power games within the organisation and outside it

the cultural school, which views strategy formation as a process rooted in the social force of culture

the environmental school, which believes that a firm’s strategy depends on events in the wider environment in which the firm sits and the company’s reaction to them

the configuration school, which views strategy as a process of transforming the organisation – it describes the relative stability of strategy, interrupted by occasional and dramatic leaps to new ones.

(Adapted from Chakravarty, 2005)

Practitioner-focus (perspectives)

- what internal process was proposed, ranging from the deliberate rational process to the less-deliberate natural process, with a focus on practitioners and their ideas:

strategy concerns both organisation and environment

strategy affects overall welfare of the organisation

strategies are not purely deliberate

strategy involves thought processes

(Mintzberg et al., 1998 (TB871 1.2.4), using ideas from E.E. Chaffee)

Schools of making strategy (prescriptive):

the design school, which sees making strategy as a process of attaining a fit between the internal capabilities and external possibilities of an organisation

the planning school, which extols the virtues of formal strategic planning involving analyses and checklists

the positioning school, which stresses the strategic need for positioning an organisation in the market and within its industry

the entrepreneurial school, which emphasises the central role played by the leader

the cognitive school, which looks inwards into the minds of strategists.

(Adapted from Chakravarty, 2005)

Messy situations

The methods used by systems practitioners can support more specific types of strategy, depending on the situation. Situations that are particularly 'messy' are more suited to strategic systems approaches than less complicated 'difficulties'.

Messy / wicked situations:

often have many interdependent factors and variables contributing to their complexity

are unclear—it may not be obvious what the issue is or how it can be improved

are uncertain—there are multiple people's perspectives involved, often conflicting and changing

Based on what I understand at this moment, I would advise people in complex situations to:

Be aware that situations involving other people are likely to be more complex than can be covered in 3 steps, but it is probably best to choose 3 overarching desires to provide clarity of purpose and guide decisions on what steps to take.

Continue asking for help, and working with others to utilise the knowledge of others and create circumstances for future improvements.

Develop adaptability to changing circumstances—this may include skills such as being resilient and resourceful.

The more we can learn about different understandings of systems, and different approaches to dealing with systemic messes, the more capable we can be to adapt to messes in our own situations. We may not be able to fully understand a highly complex situation, but we can expand our repertoire to have wider choice of tools for learning and strategising.

Challenges of using Systems Thinking

According to Meadows, D.H. (2008), Beasley (2012), Ufuk Turen (2020), and me, (2025) these are some barriers to systems thinking:

The human mind struggles with abstract thinking and information

Our mental models are restricted and unreliable

We often go for the actions that appear to show 'progress', avoiding the unknown, or things that appear time-consuming or overwhelming

Our reasoning is biased, we see what our conditioning expects us to see, and make decisions based on bias (bounded rationality)

We are easily confused and uncomfortable with uncertainty or complexity, favouring tradition, stability, consistency, that which we think we know (policy resistance)

Systematic processes make life simpler but are reductionist, avoidant of complexity in real situations

Iteration can feel like waste

We judge too quickly without understanding how others perceive the situation, limiting our ability to respond appropriately

It may be easier to see others as wrong for their views, rather than define the situation as 'wicked' or 'messy' with potential for social learning

Many people lack experience or understanding of systems thinking in practice, and therefore not appreciate its value

There are often logistical issues in environments that are not designed for systems practice

There may be difficulties in comprehending the environmental impact within our individual domains of practice

It is difficult to grasp the evolving impacts and dynamics of changes, let alone think ahead and act in an adaptive manner to those changes

The common understanding of systems does not fully reflect the potential of systems thinking and systems practice—the potential for planning and change in challenging situations, rather than just being acted upon by reified objects

Systems thinking helps us to get a bigger picture about situations (be more holistic, countering reductionism) and appreciate other perspectives (be more pluralistic, countering dogmatism). Reflecting on our boundary judgements helps us to consider the limitations of being holistic and pluralistic, thus gaining critical systemic awareness.

TB871 Figure 1.8 Adapted causal-loop diagram of the trap of reductionism in conventional thinking

TB871 Figure 1.9 Adapted causal-loop diagram of the trap of dogmatism in conventional thinking

TB871 Figure 1.10 Adapted causal-loop diagram of the trap of holism and pluralism in systems thinking

In my work as a graphic designer, gaining a bigger picture would involve doing market research, and appreciating other perspectives could take the form of feedback from clients or research into end user perspectives. Both systems thinking features were essential in my design process, and in designing the design process. I suppose that's one reason why I was drawn to Systems!

Evaluation of my current relevant skills or competencies:

Reflective practice

I am more conscious of this since studying TB872, but I think it takes practise to be aware of one's own thinking and influence on a situation

Recognising significance of boundary judgements and exploration of purpose → evaluating boundary judgements and values (reflexivity, social learning)

I am getting better at this as a result of reflective practice, and purposefully engaging in systems practice

Identifying other relevant problems when problem-solving (adapting boundaries as needed, situation-focused)

I think this may be one of my strengths, an aspect of my 'systemic sensibilities' (as described by Ison, 2017)

Using systems thinking for learning

TB872 was a great example of this as the module was designed using the principles being taught, however it did uncover some of the challenges involved in using STiP for learning in institutional settings. It was insightful learning about the development of systems for social learning and change, and being able to design such processes.

Using systems practice transdisciplinarily, as a complement to existing skills

I am very interested in the crossover between Systems and Design, and have experience in designing systems for practice but I would like to explore this more.

Facilitating interdisciplinarity, social learning and collaborative action in complex situations

It is difficult in my personal situation and through distance learning to network in a way that is not superficial but the internet is a great tool for collaborating when people are motivated to do so. It is easy to explore what people are doing in various fields of practice and utilise social platforms for collaboration. It is a bit challenging for me to gain experience in facilitation but I would like to, particularly towards finding ways for people in my position to engage in systems practice.

What is strategy?

Strategy refers to *how* you will achieve goals or objectives, or add value to a situation through orchestration and holistic vision, developing complex tactics that lead to a 'victory'. It is often utilised in business management in modern day as a means to 'win'.

A strategy creates a clear boundary between what we do *and* what we don't do.

A good strategy provides clear answers to four key questions:

Where do we compete?

(Competitive arenas / markets we will be active in—industries, product markets within industries, geographic markets)What unique value to we bring to win in those markets?

(Why do our customers choose us? What is our unique value?)What resources and capabilities do we utilise to deliver that value?

(What is in our toolbox? What are our strengths and abilities?)How do we sustain our ability to provide that unique value?

(What factors are allowing us to keep winning? What are the barriers for competitors preventing our success?)

Strategy relates to and overlaps with Systems Thinking in Practice because strategy involves being systemic (having a holistic vision) and systematic (orchestrating resources and capabilities to fulfil the vision). Boundary judgements must be made in both strategy and STiP—one has to assess what to focus on to create value, and what not to focus on. As such, they can both be seen as 'art forms' reliant on human perspective, rather than 'objective science'. Because of this facet of systemic and strategic practice, certain tools can be adopted to support reflective practice contextually with awareness that each human adds value in their subjective interpretation of the situation.

Rigour and bricolage

Rigour in this context of systems refers to the robustness or reliability of systems tools. It is important to have multiple guarantors for rigour, especially in transdisciplinary practice. Martin Reynolds (2020) outlines three co-guarantor attributes (CoGs):

1. reliability/replicability → understanding interrelationships (uIR)

2. resonance → engaging with multiple perspectives (eMP)

3. relevance → reflecting on boundary judgements (rBJ)

Reynolds also discusses how bricolage can be an effective method for engaging with STiP, linking it to the 3 CoGs. Bricolage refers to the process of crafting solutions using what you have on hand (working with others, being adaptable and resourceful, embracing learning from experiments). It is particularly useful in environments with limited resources.

We posit that bricolage is built on the four following capabilities:

(i) actively addressing resource scarcity,

(ii) making do with what is available,

(iii) improvising when recombining resources, and

(iv) networking with external partners

- Witell et al., 2017

To gain an understanding of where action is needed, first-, second-, and third-order ‘conversations’ of bricolage may be useful:

conversing with reality (conversation 1)

conversing with other practitioners about reality (conversation 2)

conversing with yourself in reflecting on the two prior conversations (conversation 3).

These 'conversations' can be seen as relating to Bawden's (2010) levels of learning, or single-, double- and triple-loop learning as discussed by Schön & Argyris (2002). On each level we gain a deeper understanding of the situation whilst reflecting further on our own subjectivity.

| Co-guarantor attributes (CoGs) → rigour of STiP | STiP heuristic | Attributes for successful bricolage (Weick et al., 2008) | 'Conversations' of bricolage | Personal notes |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| CoG1 *reliability* | Understanding interrelationships (uIR) | Trusting one’s own ideas | conversing with reality (conversation 1) | To understand a situation systemically, an analysis must occur that takes into account subjective experiences including our own (all having equal validity as experiences of 'reality') |

| CoG2 *resonance* | Engaging with multiple perspectives (eMP) | Careful observation and listening; intimate knowledge of resources | conversing with other practitioners about reality (conversation 2) | Our analysis of the situation or reality is developed through understanding of different perspectives, allowing us to act systemically—in a way that is considerate of all those engaging in the situation. |

| CoG3 *relevance* | Reflecting on boundary judgements (rBJ) | Self-correcting structures with feedback | conversing with yourself in reflecting on the two prior conversations (conversation 3). | When we understand differences in perspective, we are able to reflect on our framing and evaluation of situations, and review our actions that are informed by our framing and values. |

I will be using the STiP heuristic and the tools of different systems approaches for conversing with situations of interest, stakeholders, and myself—drawing on different experiences and practices in the bricolage of making strategy.

Area of Practice (AoP)

For my exploration of systems approaches and tools, I have selected an overarching Area of Practice:

‘Postgraduate student wellbeing in digital learning contexts’

TB871 Activity 1.15 Three dimensions to my chosen area of practice

Possible tensions:

needs of institution vs needs of students

employment expectations vs education expectations

students' professional expertise vs module teachings

amount of time available for tutors to support vs time when support is needed by students

legal requirements vs capacity for support

individual needs vs majority needs

technology capabilities vs requirements / preferences

resources needed vs financial resources

Main areas of tension may be:

Level of student needs

Capacity of tutor or other staff to support

Institutional resources available to support staff and students

It appears that use of specific systems tools in my AoP is limited, but Chat GPT has provided some examples of systems thinking elements (holistic perspective, stakeholder engagement, iterative development, feedback mechanisms) used to improve student wellbeing:

A study by Purarjomandlangrudi and Chen (2019) utilized Causal Loop Diagrams to model the interrelationships affecting student engagement in online learning environments:

A causal loop approach to uncover interrelationship of student online interaction and engagement and their contributing factorsThe Wellbeing Integrated Learning Design (WILD) framework incorporates systems thinking by using CLDs to help students co-design thriving class systems. This approach enables learners to understand the interdependencies in their educational environment, fostering a sense of agency and collective responsibility for wellbeing:

Wellbeing integrated learning design framework: a multi-layered approach to facilitating wellbeing education through learning design and educational practice

These are specifically by The Open University:

Co-designed digital resources and guidance for handling distressing content:

Participatory digital approaches to embedding student wellbeing in higher educationPositive Digital Practices Project - Co-creating resources:

Positive Learner Identities (tools to support emotional awareness and help-seeking behaviours)

Positive Digital Communities (resources to foster a sense of belonging among distance learners)

Positive Pedagogies (strategies to embed wellbeing into teaching practices.

Positive digital practices: supporting mental wellbeing (archived project)

Research paper: Positive Digital Practices: Supporting Positive Learner Identities and Student Mental Wellbeing in Technology

The OU developed an online platform that captures qualitative data on student wellbeing, providing insights beyond traditional metrics. The platform's design is informed by participatory research and learning analytics, aligning with systems thinking's emphasis on feedback loops and holistic understanding.

Boosting wellbeing and student retentionThe OU offers a micro-credential course 'Teacher Development: Embedding Mental Health in the Curriculum', reflecting a systemic approach to student wellbeing.

The OU's Faculty of Business and Law co-created a wellbeing toolkit tailored for first-year distance learning students.

Challenges and opportunities in co-creating a wellbeing toolkit in a distance learning environment: a case study

Read more about how I used AI to generate ideas for possible AoPs: https://www.alexmakes.co/blog/using-ai-for-my-systems-thinking-studies

References

Ison, R. et al. (2020) TB872: Managing change with systems thinking in practice. Available at https://learn2.open.ac.uk/mod/oucontent/view.php?id=2303519.

Reynolds, M. and the module team (2020) TB871: Block 1 Tools stream, The Open University. Available at: https://learn2.open.ac.uk/mod/oucontent/view.php?id=2438584 (Accessed: 20 May 2025).