Encountering unknowns and knowns - TB871 Block 1 (People)

Accepting unknowns

In the 'People stream' of TB871 Block 1, we explore the limitations of the human perspective on what we can know about complex situations—coming to terms with the ever-present 'unknowns' in complex situations and how practitioners can act as 'bricoleurs' in those situations, using what we do know and have access to.

It is, of course, difficult to identify unknowns and this can naturally result in a feeling of unease or anxiety. For example, I do not know how others perceive me which makes the performance of being a social human a constant learning process—learning what is acceptable to some people, learning how to avoid negativity, learning how to adapt to different situations, learning how to do all this whilst maintaining my mental health and valuing my own needs.

Reflecting on my unknowns does make me somewhat uncomfortable. I am generally excited about learning but that can easily turn into anxiety when knowledge is out of reach or too challenging. Perhaps my perception of the feeling can be changed depending on the context and beliefs about the situation. This makes me think that there are ways of confronting unknowns, maintaining awareness of them as possibilities that will benefit, even if the unknown turns out to be something we consider negative. Either the harmful unknown is affecting us without our knowledge or we gain understanding of how it is impacting the situation, and therefore better understanding of how we can improve the situation.

There are many situations in which things are happening without our knowledge that do affect us greatly, such as governmental decisions or cultural shifts. For these, we rely on others to communicate their understanding and experience of these changes. It would therefore be beneficial to work on creating environments in which honest, authentic, free communication is supported and encouraged. That way, we can all benefit from better understanding situations that affect us. The opposite is also true—we need to be aware of factors that limit communication and allow misinformation to proliferate.

There isn't a way to fully know what we don't know until we are exposed to it, by which time we can categorise it as known to some extent. How can we be more aware of the possibility of unknowns, and the necessity to keep an open mind to learning those things we don't know? Is it necessary to look for unknowns, unless it is a factor that affects the situation in a tangible way? If it does have such an effect, would it not be in some way known?

Unknowns in my Area of Practice (AoP)

My AoP is postgraduate student wellbeing in digital learning contexts, and there are multiple variables and unknowns that are of concern when addressing the subject. For example:

Students:

What wellbeing means to them

To what extent individual differences and personal circumstances affect wellbeing

How interventions affect them in the short and long term

Staff:

What their capacity to address issues regarding wellbeing is, alongside their regular workloads

To what extent they have a responsibility for the wellbeing of postgraduate students

Institutions:

To what extent facilitation of wellbeing measures will be effective and worthwhile, particularly in the long term

How individual student needs can be met when metrics for success are primarily quantitatively measured

Wider environment:

How student wellbeing impacts workplaces, families, communities

To what extent wellbeing of students impacts their future prospects and access to opportunities

To what extent social support systems outside of educational institutions bear the burden of poorly-supported wellbeing of students

In TB872, my situation of concern was related to EDIA in postgraduate curricula and there were similar issues with this—it can be a subjective area with some contention about who is responsible for it and how it can be implemented. Understanding what the major issues in wellbeing / EDIA are, and who is most affected, can be ascertained through statistical analysis using data such as comparative pass rates but this does not provide the full picture.

Based on the information that is available, it has been determined by institutions like the OU that certain practices would support inclusion and equity goals. Unfortunately due to structural barriers, pedagogical traditions, technological limitations, cultural norms, inclusive practice can be challenging to implement which is why attempts have been made to embed certain features into the educational experience, into teaching practice and module materials. Wellbeing may well benefit from similar attempts.

There is a lack of research into what constitutes an effective intervention (and what 'effective' even means), possibly because there are so many variables in the study of 'wellbeing'. However, by setting realistic boundaries for systemic inquiries, I hope to be able to find out how different approaches can support improvements in some aspects of postgraduate student wellbeing, particularly in digital learning contexts.

Unknowableness of the world

Systems thinker Heinz von Foerster (2003) stated that 'soft sciences' cannot fall back on reductionism as 'hard sciences' do, because they are trying to understand situations where the complexity arises in the interactions between the parts. In TB871, it is stated that 'the unknown is not just a temporary or local state that will only persist until science catches up'. Five reasons are given for this:

overwhelming complexity of networks

It is suggested that anticipation of outcomes is unrealistic, and strategists should focus on preparedness based on available information.

Comfort and stability is more of a social achievement that is created and maintained collectively, than a given

We need to consider what we might believe to be underlying stability, and what could happen if it suddenly changed

processes that control stability and instability

There are tipping points at which drastic change can occur, and big change can happen very quickly

We need to be aware of the potential for information in complex networks to flow in a variety of ways that can be affected by individual responses, connectivity and environmental conditions

It can be challenging to identify the aspects of connectivity that should be considered

unpredictability of developing patterns of relationships

This can be a huge unknown as interactions at various hierarchical levels result in unexpected emergent behaviour at other levels

A lot of behaviour is unstable and unpredictable, and many interactions are complex, influenced by many variables

Revealing blind spots and developing awareness of the impact of individual assumptions can increase resilience under unexpected circumstances

‘social messes can be wicked’

A multitude of perspectives on a situation multiplies the complexity and difficulty of 'improving' the situation as each person has a different boundary and framing of the situation and different opinion on what improvement means

Power imbalances in complex situations often do no allow for the consideration of all perspectives involved which limits ability to develop a systemically desirable outcome

situations are not situations

Our interpretations and conceptualisations of situations are not representative of the real world

Situations are constantly changing, especially as we intervene, and we may not be able to keep up with fully understanding the situation, organising and designing for the situation

Feedback on situations is always delayed and therefore an inaccurate representation of the current situation

Human language limits our capacity to understand and communicate about situations (even the term 'situation' is culturally informed and specific to a way of thinking/talking)

Responding to unknowns

In situations that feel scary and unknown to some of us, others may enter with greater confidence because:

they have experience with similar situations, and therefore an understanding of the possibilities in such a situation

they have a toolbox with a range of appropriate tools for different potential issues

they have relevant knowledge and skills

they have planned for issues that have a likelihood of occurring in such situations

they know their role in the situation

These are some of the aspects of strategy that may be useful when dealing with complex situations. However, the more experienced and knowledgable we are, the more likely we are to not see elements of a situation that are outside of the mental models we have developed. Our expertise can become 'brittle' with experience (Keestra, 2017). There is a tension between the confidence of experience and the consciousness of uncertainty.

Openness to our humanness may help us to go beyond technical rationality and embrace the messiness of the 'swamp' (Schön, 1987). Strategic thinking may be enriched by extending the 'variety of epistemologies' to include 'experiential, presentational and practical as well as the propositional' (Heron and Reason, 2008, in Reynolds, M. et al., 2020).

By engaging in TB871 activities so far, I have found it helpful to clarify some of the factors to look out for in regard to 'unknowns' as it somehow makes them more 'knowable'. However, I am concerned about falling into the trap of feeling too confident about unknowns or being blind to possibilities.

I think the complexity of situations is further complicated by practitioners' decisions—which areas are worthy of exploring, what we have capacity to explore, and what kind of intervention is appropriate especially considering the recursive and dynamic relationship we have with situations. Our comfortability does affect our choices, and it is worth keeping that in mind when choosing a strategic approach for managing the situation. If the point is to find a systemically beneficial 'solution', then we may have to compromise on our comfortability or collaborate with people that are more capable of working with appropriate approaches.

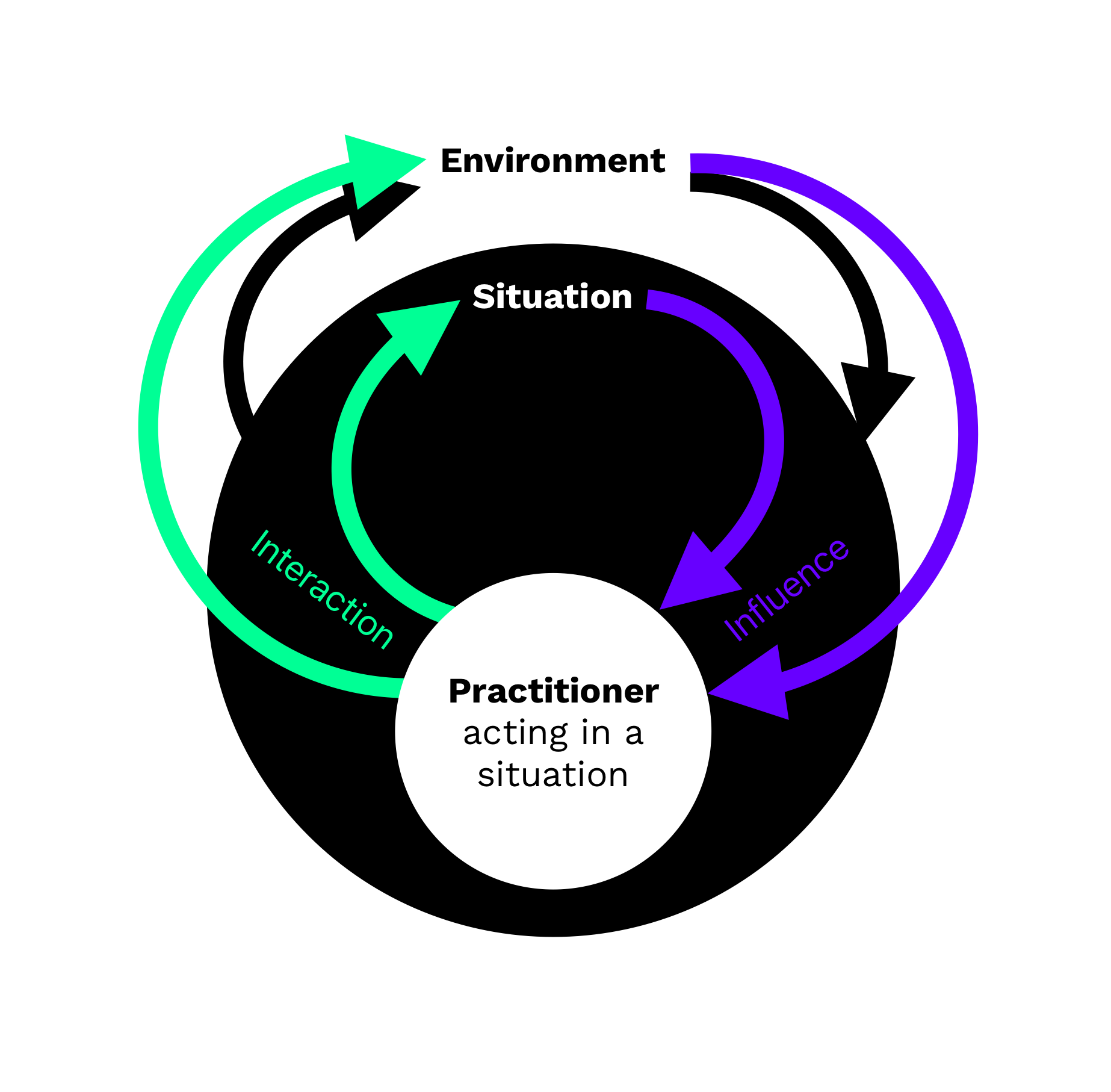

In a 'wicked' situation, there should be various skillsets and experiences to co-create with, so an important aspect of my own personal development would be to develop collaborative, communication, and facilitation skills in order to access the wealth of resources abundant within that complexity. I hope to maintain awareness of the fallibility of my own assumptions and the limitations of human cognition and perception, whilst utilising my skills and experience to develop knowledge through purposeful activity—'transforming complexity' by constructing systems via the development of my systems literacy (developing my 'niche' as I and the environment in which I practice recursively impact each other as we change).

'…when speaking to almost any scientist about how their research comes about, most will reveal quite quickly how the tracks to and from the larger wilderness that sits beyond the pristine lab room have tangible influences on the science that gets done. This wider sphere of influence includes outer arcs of attention – other people, funding bids, organisational hierarchies, institutions and time – and inner arcs of mental processing, psychology and personality.'

- TB871 (Reynolds, M. et al., 2020)

TB871 Activity P1.9 Niche as a way of acting v2

Our ability to abstract, conceptualise and create stories about the world has been an important part of our social world and development as a species. It has also been a weakness such as in our reification of concepts, attachment to the stories we tell, and difficulty in differentiating between the 'maps' and the 'territories' (Korzybski, 1931).

Reflecting on my own experiences, I realise that there were several instances in my childhood and adulthood where I had to discard my model of the world. This ultimately changed my worldview and lifestyle, my interpretation of my environment, my interactions with people and perception of myself. I realise that there are reasons why we tell stories to ourselves and others. They keep us safe, protecting our minds in a world that is incredibly interconnected and complex, overwhelming and frightening. It can be mind-breaking to stumble upon the realisation of just how creative we are in the formation of perception and understanding of the world, but we can work towards it gradually and learn from traditions, philosophies and cultures that have explored these topics for thousands of years. I am in two minds about whether it is ideal to create new stories in place of the emptiness of (de)realisation. In any case, I am not sure that we have a choice in the matter.

Integrating novelty - being a bricoleur

I think it is a part of my personality to develop interests that I obsess over until I eventually get sick of them and begin to yearn for simplicity. For example, when I learnt how to use a sewing machine, I spent months upcycling second-hand clothes, *needing* to perfect the craft. EVERY GARMENT IS A CREATIVE OPPORTUNITY, my brain would shout at me. Eventually other hobbies took precedence and sewing fell to the wayside. I develop similar obsessions with tools such as personal knowledge management and organisational tools. YOU COULD BE SO ORGANISED—YOUR LIFE WILL BE CHANGED, brain keeps shouting. It's very loud. Something in my being urges me to collect, to organise and improve, and fix things. Perhaps some evolutionary trait, a genetic predisposition towards creativity for control, perhaps my anxiety and neuroses—most likely all of those combined and somehow connected.

Knowing that improvement was possible, was enough reason to keep doing the thing if my body would let me. It feels amazing to experience the levelling up of skills and knowledge, the ability to interact with the world differently and have a new way to feel control over my life. In actuality, I think the feelings I had were not controlled—my obsessions are addictions that I have to have good reason to stop, usually replacing with a new thing that gives a sense of control over my life. As such I don't think I have real ownership over the approaches apart from the unique way I would integrate it into my circumstances, gradually incorporate into my way of knowing after a lot of repetition.

I love learning about new tools and new ways of doing things. I do need to be wary of becoming attached to any one idea, and be more mindful of where each approach might be appropriate or could be adapted—this itself is an approach that can be practiced and learnt, so I will focus on practising the creative adaptation of tools rather than prescriptive use. Reflecting on my past experience with new tools, I do have a history of creatively adapting once I have a strong grasp of the basics. It can take me some time to fully understand, especially as ideas and approaches are interpreted so differently in various situations by different people. I am purposefully choosing to frame the learning process as an exploration of diversity through which I can hopefully develop my own stance, preferences, and ability to contextualise approaches in a way that continues to be supportive of the inclusion of a variety of perspectives.

Karl Weick (1993) suggests that a 'bricoleur' has confidence in the self-correction of their practice and organisational structures that they design because they had good knowledge of their chosen materials, methods and approaches. However, when working with the relatively unknown, they engage in an enquiring way through which they deepen their knowledge of tools and processes whilst practicing. They are therefore adaptable and flexible in their designs and use of materials and methods, depending on the context.

Based on my studies of TB871 so far, some challenges that I might face in acting as a bricoleur, and in the integration of systems approaches into my practice, might be:

Utilising my understanding of systems from both TB872 and TB871 contexts, whilst staying focused on the specific meanings and purposes of my current module

My 'traditions of understanding' (Ison, 2017) conflicting with the framing of systems thinking in the module

Lack of relevant experience or access to situations in which complexity is managed and strategised for

Limitations of engaging with, and learning from situations, from a distance

Lack of time and resources to fully engage in systems practice in relevant contexts, and experiment with approaches

Anxiety and overwhelm of engaging with unknowns, with time constraints and limited feedback

However, acting as a bricoleur, my practice could benefit from:

My lack of attachment to my situations of interest due to not being employed in the field, and therefore ability to be less biased in my engagement

My recognition of my unique perspective in my area of practice, enriching potential understanding of the situation for collective learning

The freedom from expectation that comes from being able to purposefully draw on my own experience, and being creative in my use of tools

My creative career experience

References

Reynolds, M. and the module team (2020) TB871: Block 1 Tools stream, The Open University. Available at: https://learn2.open.ac.uk/mod/oucontent/view.php?id=2438584 (Accessed: 20 May 2025).