Learning Systems for Improvement of Inclusive Practice

Adapted from writing for TB872 Managing Change with Systems Thinking in Practice (The Open University) 2025-04-22.

Engaging with my situation of concern

My situation of concern (SoC) for the TB872 module ‘Managing Change with Systems Thinking in Practice’ related to challenges associated with Equity, Diversity, Inclusion, Accessibility (EDIA) at The Open University (OU), particularly in the design of postgraduate Systems Thinking in Practice (STiP) curricula. I became concerned when I realised at the start of the module that there was little diversity in lineages of Systems being taught, I felt that my queries on this were dismissed, and not enough of the course material addressed issues of power and institutional constraints to systemic change. I felt disempowered until I found out that others felt like me. Engaging in systemic co-inquiry motivated me to continue. I discussed my SoC with students and staff, reviewed the OU’s EDIA policies and practices, the development of Systems curricula at the OU, and evaluations of the course creators’ praxis in creating reflexive learning systems.

Ray Ison and Chris Blackmore, authors of Systems modules at the OU, recognise that there is an ethical issue with Systems education—it is difficult for some people to do STiP because of their circumstances and factors such as institutionalised ideologies, cultures, and power relationships (Ison and Blackmore, 2020, Part 2 Box 2.9). We (students) learnt that STiP thrives on plurality and is undermined by exclusion (Ison, 2017, p. 142, 151, 156, 206-27, 297, 300-301, 319). EDIA is therefore a crucial requirement. Additionally, the OU provides services to a diverse range of students—many from marginalised communities that would benefit from improved inclusive practice.

My choice of SoC was considered risky by some because it directly challenges those that hold power in the situation. For example, in a group chat for OU Black STEM students, one student (Anonymous, 2025) expressed their concerns regarding lack of representation for women and non-white people, but recommended avoiding the topic of race in TB872 assignments. This tells me that there are stakeholders affected by such issues, but it is difficult for them to address these concerns. I discussed my SoC with TB872 student Rachel Lemonius (2025) who described the situation as ‘positively messy!’ and gave feedback to support my reasoning with examples. As I engaged further in systemic inquiry, I discovered many different perspectives and experiences that I felt were important to address. I related to the concerns of Louise Hartley (2025), another TB872 student, about those that may be too vulnerable or unprepared for epistemic learning which Ison and Blackmore (2014, p. 4) say relies on destroying and rebuilding worldviews. Although somewhat inefficient for in-depth inquiry, the TB872 module forums were useful for starting a lively discussion about my SoC, and identifying themes. Several students found difficulty engaging with the unnecessarily complicated use of language in module materials, complexity of multi-level braided inquiries, and often being unsure of what was expected.

Figure 1: Selected quotes from forum thread (Magombe A. et al., 2025)

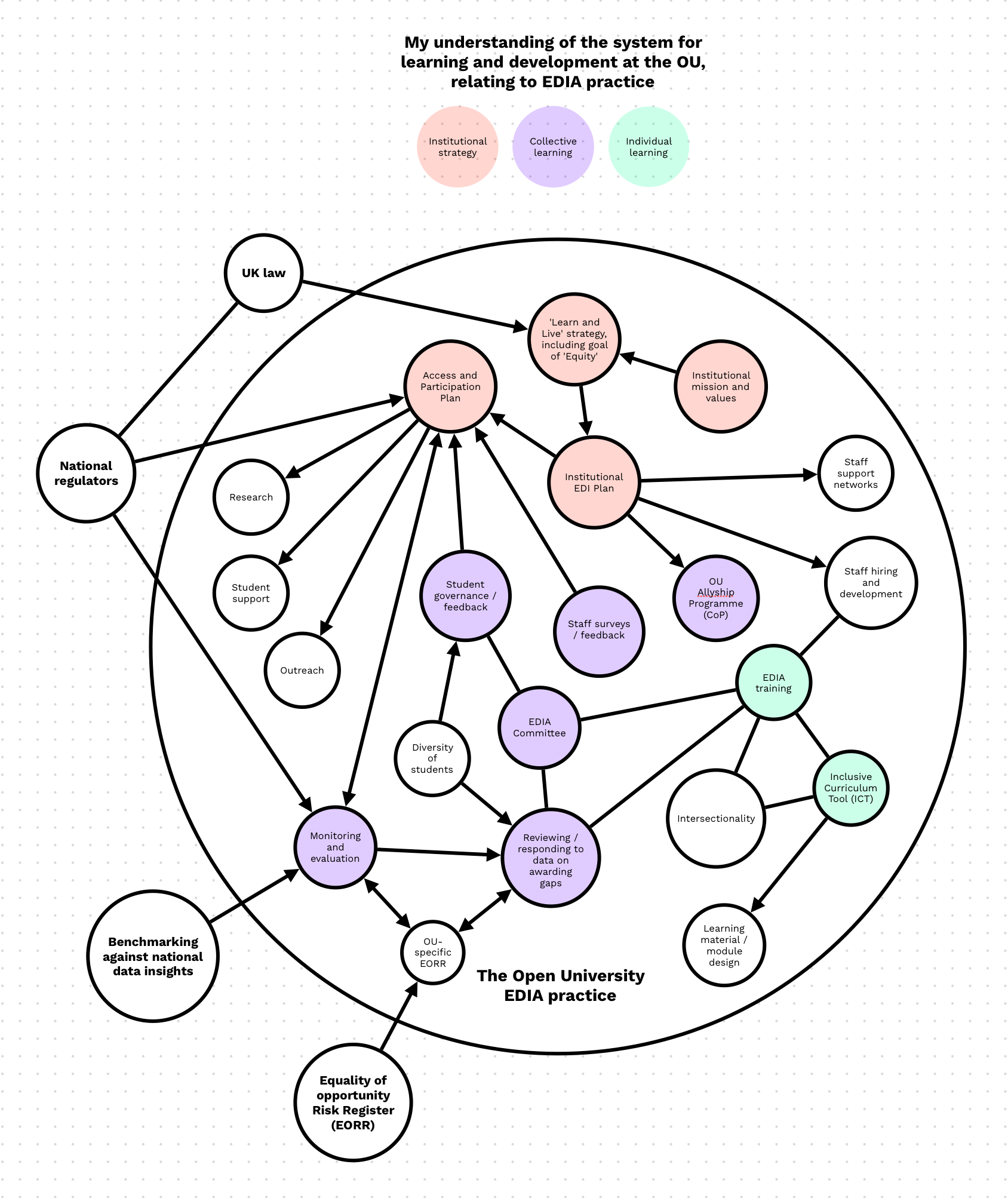

As an end-user, I have limited insight and information on the situation, so social learning has been invaluable. In discussion with Nicole Lotz (2025), Deputy Director of STEM EDIA at the OU, I found that OU EDIA systems and practices appeared to be well designed. The OU’s documentation (2022-2024) on creating an inclusive learning environment shows that there is not a ‘lack of a purposeful system’ but possibly a structural or ‘system-determined problem’.

Systemic inquiry is an open-ended way of learning about a situation alongside those that have a stake. Through systemic co-inquiry, stakeholders could identify concerns specific to their self-defined learning systems and systems of interest. Engaging in systemic inquiries during TB872 has made me more accepting of uncertainty and complexity because I am more open to possibility by purposefully taking an inclusive stance. This is supported by Ison (2017, p. 251, 265) who argued that shifted perspectives towards new ways of thinking and knowing can facilitate cooperative adaptive learning, potentially becoming a feature of governance. Engaging in co-inquiry, I have felt a confirmation of our interdependence, shared governance of our situation, and expanded potential for influencing adaptive change.

The Critical Learning System (CLS) approach is the ‘design, establishment, maintenance and development of self-referential, or critical, learning systems’; a Critical Social Learning System (CSLS) is a group of people purposefully learning together, inquiring systemically and accommodating their diversity in the process of critically improving the situation including the CSLS itself (Bawden, in Blackmore, 2010, p. 43, 94). I believe that a purposefully reflexive system of development, like a CSLS, can support challenging of biases (through critical reflection and reframing of contexts), and embedding of EDIA practice that is collectively determined to be systemically desirable. This is particularly powerful in educational institutions where accommodation of worldviews can have strong trans-systemic paradigmatic impacts. If we can embrace the uncertainty of an unknown destination in systemic co-inquiry, we can uncover new opportunities for change in situations, and in ourselves.

A Learning System Design

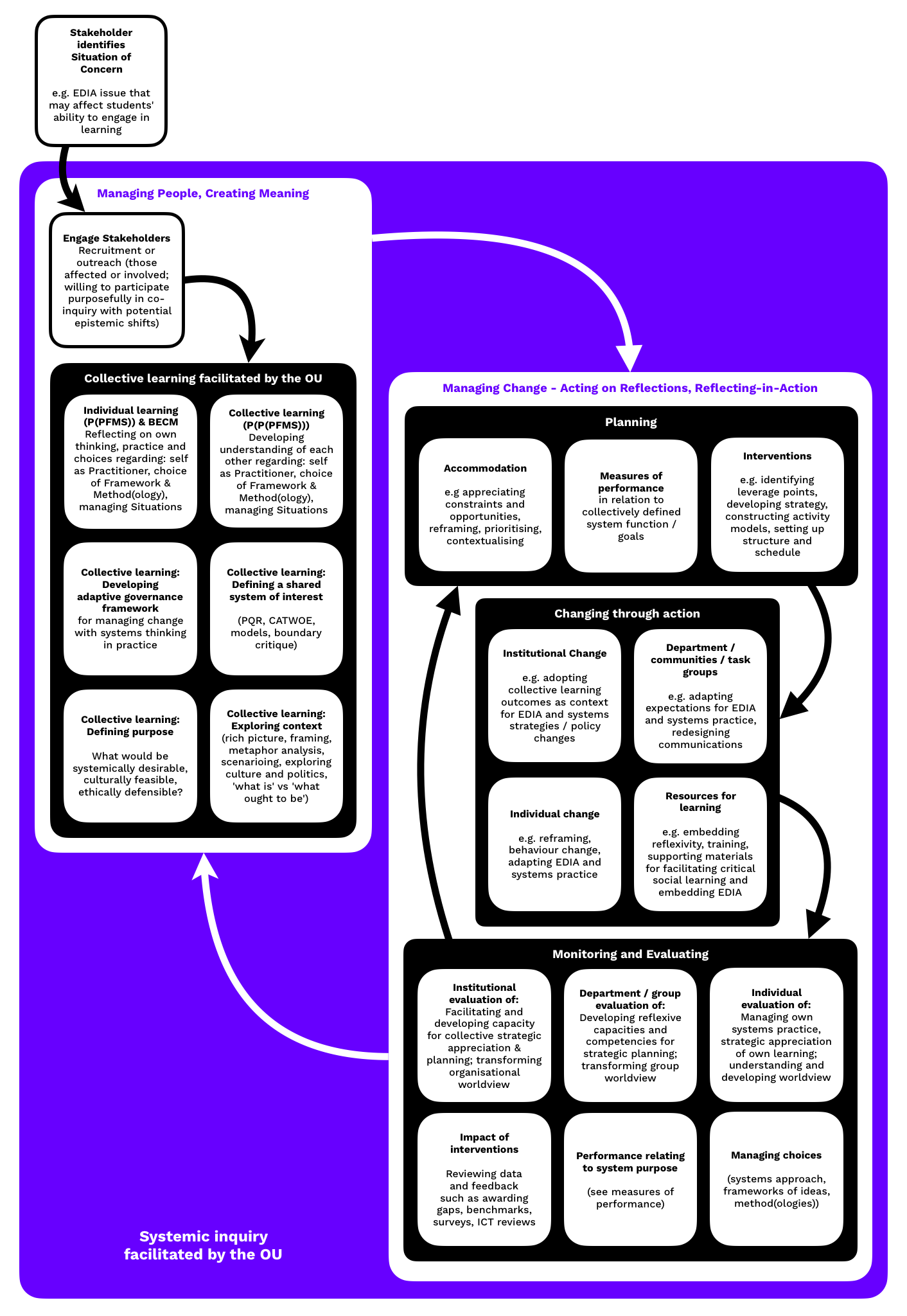

Figure 2: a system to improve EDIA practice at the OU using a CLS approach in order to achieve systemically desirable outcomes for all stakeholders and wider environments influenced by the institution.

Enabling STiP

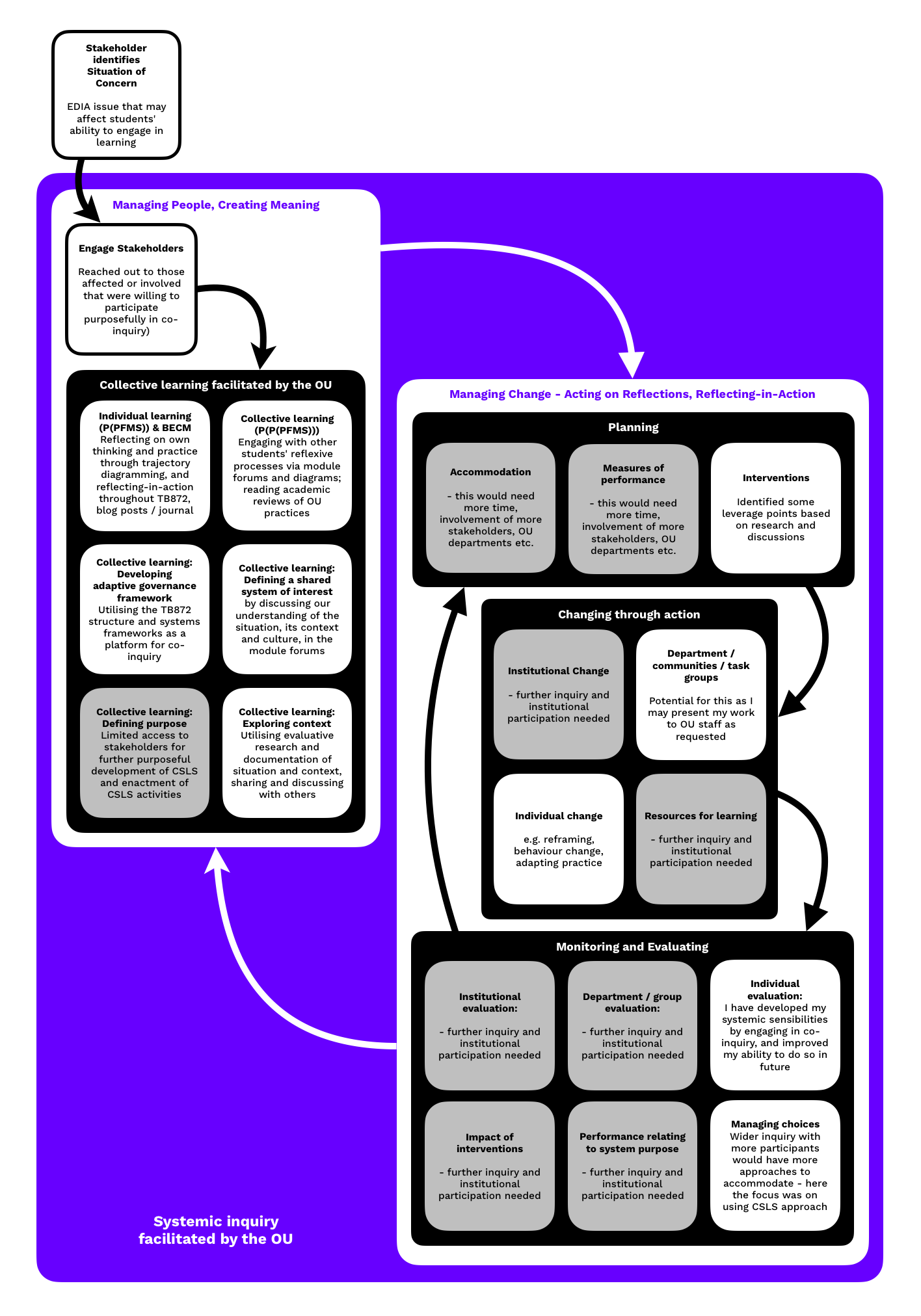

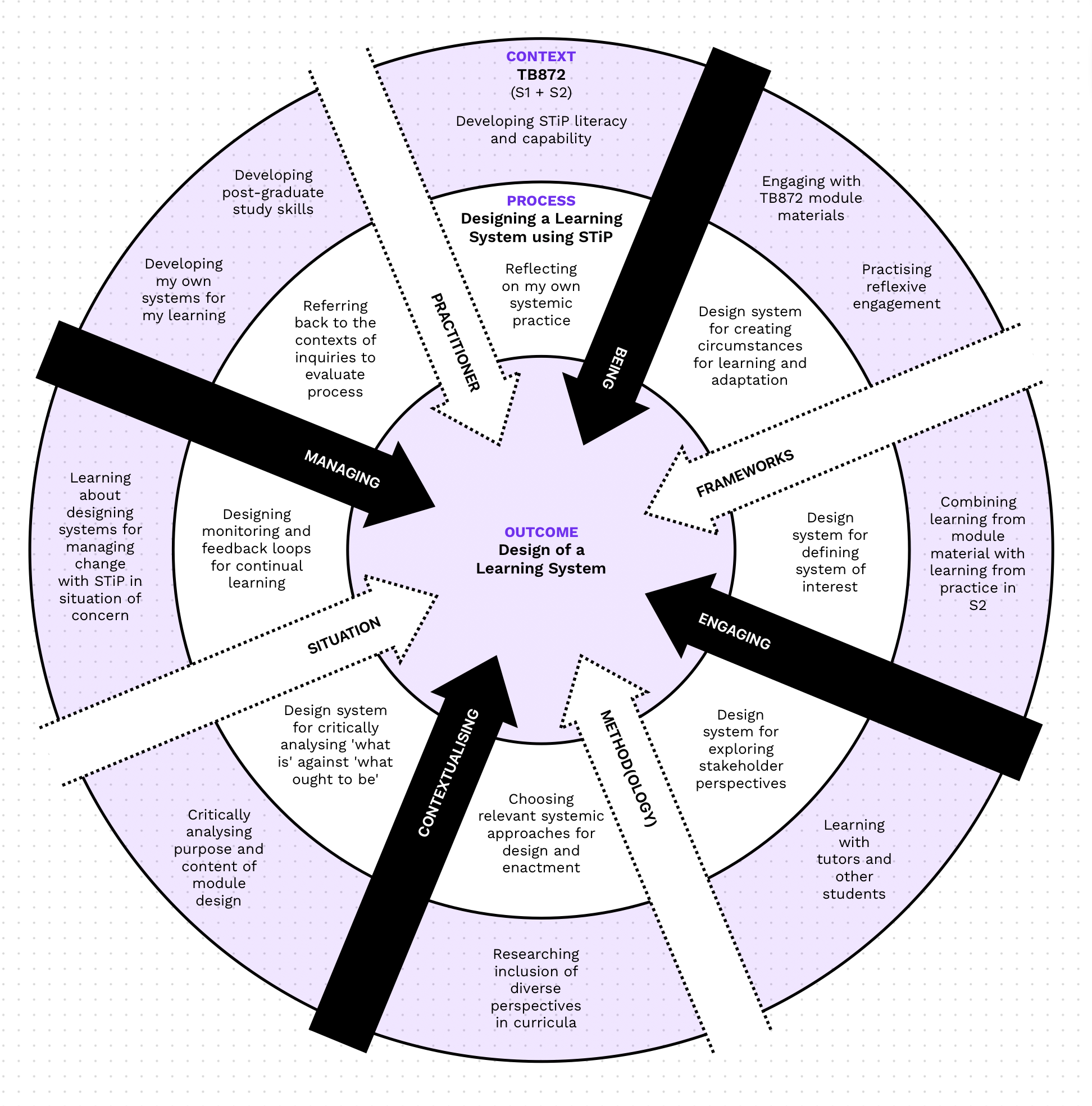

My learning system design (Figure 2) is based on my current understanding of frameworks as learnt through TB872 and my experience of their features. More relevant choices may be made through further co-inquiry. Retroactively comparing my activities to those in the designed system (Figure 3), I can see that the learning system can enable STiP.

Figure 3: A record of my enactment of the TB872 learning system, measured against my conceptual model of activity (Figure 2)

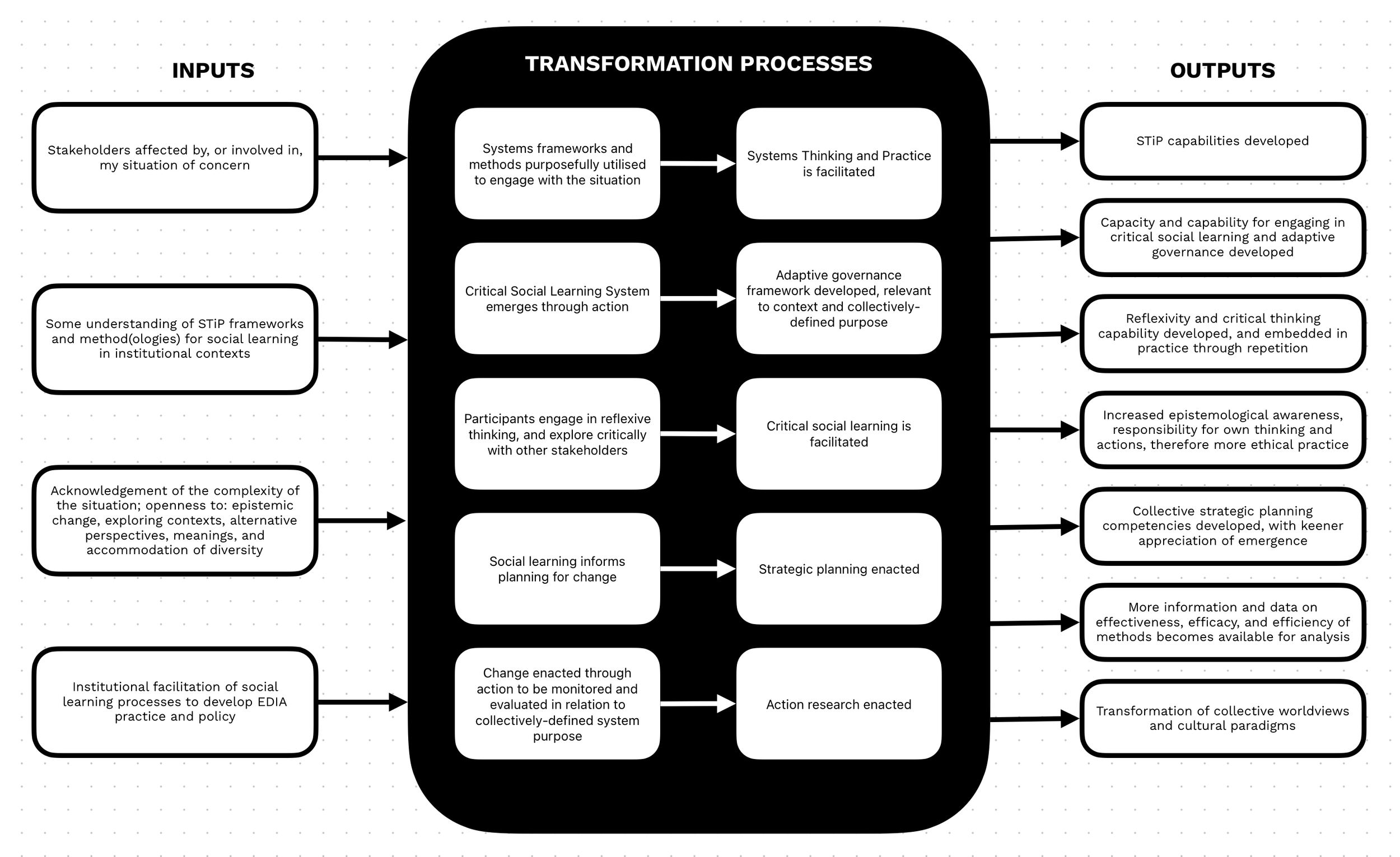

Transforming processes

If activities were enacted as suggested in my learning system design, there would be multiple transformative processes occurring throughout learning cycles (Figure 4). The inputs—stakeholders, purposefully selected Systems frameworks to manage acknowledged complexity, and institutional facilitation—enable functionality. Purposeful action begins transformation of actors into a CSLS, its iterative transformative processes modifying standards and values through appreciation of change over time as STiP and inclusive practice for systemically desirable outcomes is normalised and institutionalised.

Figure 4: Transformation processes in my design of a learning system for improving EDIA practice at the OU

Creating circumstances for change

STiP relies on suitable circumstances for enactment and emergence either existing or being created by practitioners, such as timely responses to emergent understandings or adaptability to specific framings and worldviews (Ison et al., 2014). This is not always possible, and is a concern relayed by a STiP student (Hartley, L., 2025). Considering wider systemic context—academic traditions, cultural norms, and/or institutional structures—may mitigate their influences.

My S2 inquiry (managing change with STiP in my SoC) revealed numerous potential areas for improvement relating to institutional change, EDIA practice, professional and departmental practice, and STiP curricula design. I have incorporated suggestions from others into my learning system design, and identified several leverage points for development through social learning activities (Figure 5).

Figure 5: My understanding of the system for learning and development at the OU, relating to EDIA practice

Inquiring individually

My aim was for my design of a reflexive learning system to inspire ‘design turns’ and support cognition and learning on multiple levels (Bawden, 2002, p. 29):

Learning about the situation

Learning about how we are learning

Learning about the nature of the beliefs and values that we hold that influence the way we conduct learning at the other two levels

The ‘juggler’ heuristic supports understanding and communication of complexity in managing a situation, and the Practitioner-Framework-Method(ology)-Situation (PFMS) tool provides a helpful prompt for reflecting on practice and recognising choices available in a situation (Ison, 2017). I recommend that, as in TB872, PFMS is adapted to reflect the level of reflection, for example:

PFMS: Reflecting on my practice or ‘what I do when I do what I do’ (Ison, 2017) as I consider that I am always a part of the situations I engage with (second-order thinking)

P(PFMS): Reflexively thinking about how I think about my reflections on my practice, as I consider the impact of my worldview, beliefs and values on my understanding and framing of a situation

P(P(PFMS)): Thinking about the practice, traditions and worldviews of others in the situation as I consider that systemically desirable change is achieved through social learning and collective action

Inquiring collectively

To facilitate a CLS approach, stakeholders must purposefully utilise relevant frameworks and methods. Clarity regarding complexity and purpose may be developed through group activities that explore differing traditions of understanding. I have found sharing diagrams of trajectories amongst fellow students useful for exploring worldviews, and developing ‘interdisciplinary dialogue’ across our ‘landscape of practices’, as recommended by Ison and Blackmore (2014, p. 5, 9), Maiteny and Ison (2000, p. 580) and Wenger-Traynor (in Blackmore, 2010). A shared system of interest is defined, and frameworks and methods are contextualised, by exploring perceptions of context towards the development of strategic plans for co-adaptive measures in relation to the ‘suprasystem’ (and in defining the suprasystem, defining themselves as a purposeful system) (Bawden, 2002, pp. 51-53).

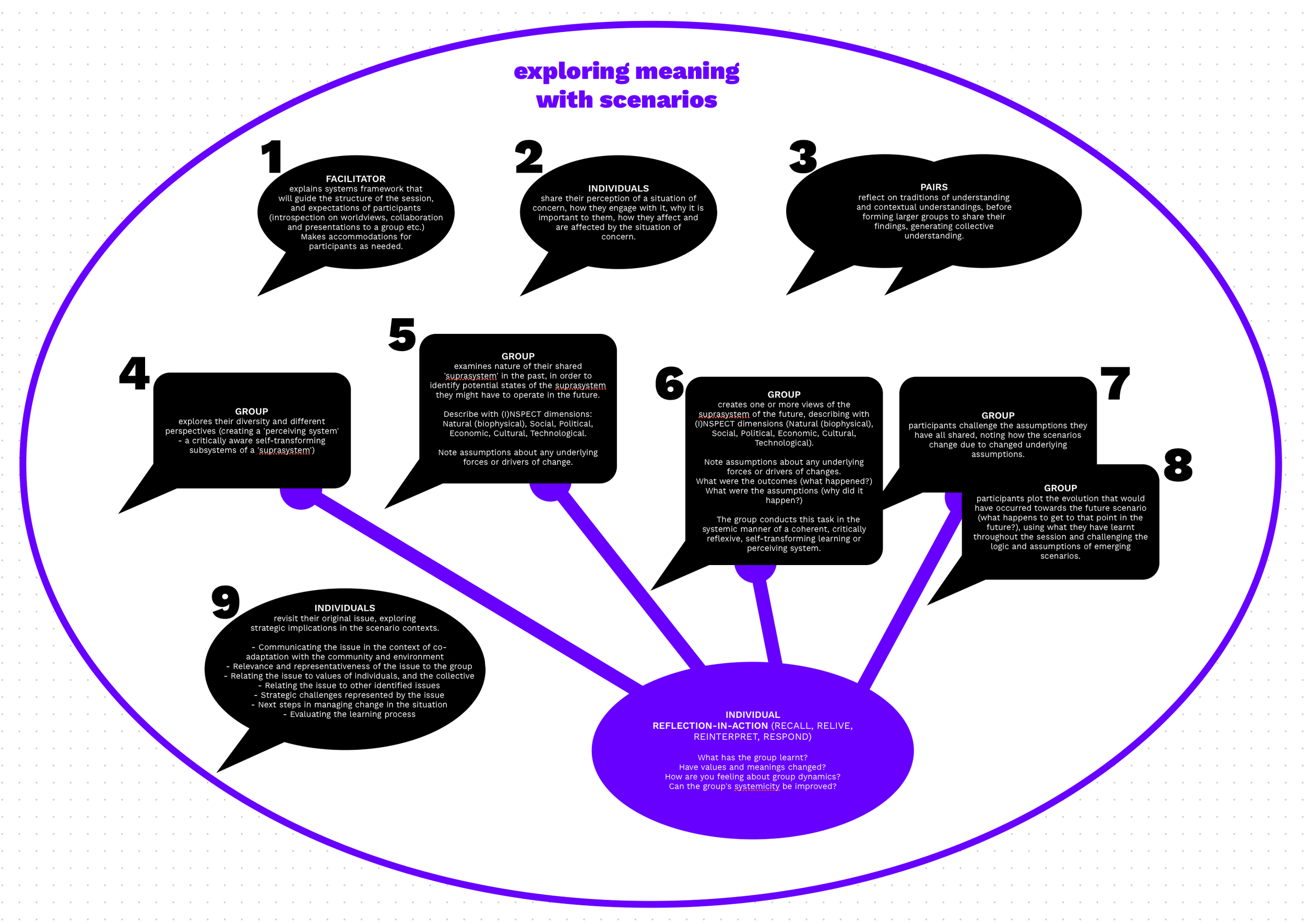

Methods such as ‘metaphor analysis’ and ‘scenarioing’ can support sharing and evaluation of understandings whilst mitigating distortion of communication and creating space for meanings to emerge. However, effectiveness is likely sensitive to starting conditions and contexts (Ison et al., 2014, p. 626, 629), and as with many Systems methodologies, models for praxis need testing and development. The process may be complex and time-consuming, requiring differentiation for varied needs. As a subsystem of my learning system design, I adapted features of Bawden’s (2002) scenarioing workshop for use in social learning activities (Figure 6), accommodating student concerns and recommendations from Veuger et al. (2023) about clarity and consent by ensuring that explanations and accommodations are made by a facilitator.

Figure 6: Activity diagram for systematic social exploration of meaning using scenarios (Adapted from Bawden, 2002)

Monitoring effectiveness

The effectiveness of the system can be determined in relation to the system function as in the root definition, and as the definition is refined by the system over time, in relation to stakeholders changing standards and values (Vickers, in Blackmore, 2010; Checkland et al., 2006). I include reflexive thinking, and recursive monitoring and evaluation activities for practitioners to reflect on their ‘juggling’ performance as well as changes in the situation, and development of the learning system itself. This is important for the maintenance of an ethical system that effectively, efficiently and efficaciously fulfils the system purpose, and for the system purpose and function to be evaluated by the system as systemically desirable and culturally feasible.

Designing the learning system

I used the CLS approach to explore one possible way of using learning systems for improvement in my situation of concern, referring to the work of Bawden and Ison who have outlined the approach in Blackmore, 2010.

I also refer to the work done in designing a system for learning, in the form of the OU Systems curriculum, by Ison and Blackmore (2014). As a student on an OU Systems course (TB872), I evaluated the use of this approach based on my experience of the module, feedback from students’ ‘social learning system’, and my TB872 systemic inquiries, to design a learning system for improvement. As a means of learning ‘socially’, I also took into account evaluations of the OU Systems curriculum design and department strategy (Maiteny and Ison, 2000), and The Open University EDIA tools and practices (The Open University, 2022-2024; Veuger et al., 2023).

I made use of Systems concepts, tools and methods to inform my praxis as I progressed through TB872. There were limitations to what I could achieve through online communication with S2 stakeholders, and my personal circumstances (disability, distance learning, limited time) constrained my ability to engage in inquiry to the level I would like, but it was still a valuable lesson in contextualising and adapting my approach.

Figure 7: My process of designing a learning system using STiP, in the context of TB872

Action-learning with Soft Systems Methodology (SSM)

SSM heavily influenced the design of Systems modules at the OU and it is considered a suitable model for systemic inquiry that allows exploration of complex issues and different perspectives in a critical social learning context (Ison, 2010, p. 76).

On the design of Systems modules at the OU, Ison (2007, p. 8) states that Mode 2 SSM (an internalised SSM model for interaction) is adapted so that students move from single- to double-loop learning by both learning about and participating in the design of learning systems. It can be said that triple-loop learning also occurs through the epistemic level learning as referenced in Kitchener’s (1983; Ison and Blackmore, 2020, 3.3.4) theories that influenced the CLS approach. Bawden developed these levels of learning by outlining transformations that can occur (Ison et al., 2014, p. 629). I see these levels of learning and transformative possibilities as a useful indicator of potential for continued change. Ideally, in practice, the thinking and learning style would shift between the different levels over time. This ability can be developed but also prompted, as in my design.

Table 1: Variations of ‘levels of learning’ as described by Kitchener, Schön and Argyris, Bawden and Ison et al.:

|

LEVEL OF LEARNING (Kitchener, 1983; Ramage & Blackmore, 2020, 3.14) |

Description |

Example |

LEVEL OF LEARNING (Schön & Argyris, 2002) |

Description |

Example |

LEVEL OF LEARNING (Bawden, 2010; Ison et al., 2014, p. 629) |

Description |

Example |

|

Cognition |

Learning about the matter to hand |

What is the situation around me meaning to me? |

Single-loop learning |

Changing behaviour - action |

Am I doing things the right way? |

First-order transformation |

Scenarios and strategies |

Developing strategic appreciation |

|

Metacognition |

Learning about how we learn about the matter to hand |

What is my thought process in understanding / interpreting the situation? |

Double-loop learning |

Changing thinking - reframing |

Am I doing the right things? |

Second-order transformation |

Planning and learning |

Developing strategic planning competencies |

|

Epistemic cognition |

Learning about the limits to learning |

How do my worldview, beliefs and values limit my thinking and learning? |

Triple-loop learning |

Changing perspectives - transformation |

How do I decide what is right? |

Third-order transformation |

Epistemes and culture |

Developing reflexive foresight competencies |

Avoiding systemic failure

Many of my learning system’s features require institutional support, as do my recommendations for creating suitable circumstances, and other recommendations such as those from Maiteny and Ison (2000). Ison and Blackmore (2014, p. 5; 2020, 2.5.1 Box 2.10) acknowledge that it may not currently be possible to create ideal ‘learning systems’ (or curricula) that monitor, organise and transform themselves (Bawden, 2002, p. 29), within existing institutional structures. This may be by design—a function of a system for perpetuating ‘command and control’ mechanisms, undermining collective ability to make systemic change (Ison, 2017, p. 229; Ison and Blackmore, 2020, Box 2.9; Magombe, A., 2025, 4 January).

The OU does have a history of inclusive practice, has resources for facilitating CLS (within certain parameters), and has attempted to implement and embed EDIA policy horizontally across departments. Unfortunately, the necessity to comply with EDIA policy may constrain authentic engagement with, and integration of, inclusive practices through an epistemic framework (thus creating further EDIA issues).

Ison (2017, p. 332) proposes taking a design turn by using Systems frameworks to effect second-order change and shift possibilities of cultural feasibility. The OU aspires to meet specific goals in regard to EDIA which can potentially be met by facilitating CSLS which are inherently inclusive of diversity. Although certain conditions are preferred for fostering suitable circumstances, a CSLS is self-organising, self-transforming, and shapes its own systemically desirable functionality. This takes into account context, environment, and institutional function. It is therefore beneficial for stakeholders, and for avoiding suprasystemic failure. Institutions such as the OU must decide if they want to remain stagnant on a level of compliance to laws, or if their constituents value paradigmatic change that could be institutionally facilitated.

There is also the potential for staff departments, student faculties or support groups to gradually evolve independently into critically self-aware, self-organising and self-transforming subsystems (Bawden, 2002, p. 16), creating democratic hubs of resistance against institutional oppression (Sidman-Taveau and Hoffman, 2019, p. 128).

Impacting the environment

By facilitating second-order thinking, learning and development is more epistemic and systemic—stakeholders are able to have a deeper understanding of the situation and their roles in it. They would develop invaluable skills for critical reflection and inquiry, becoming more conscious of the systems they are a part of, expanding and utilising the choices they have within those systems. They would be able to make decisions that are based on awareness of subjective interpretations, the value of plurality in deciphering and creating meaning, and an ethical stance that is more considerate of diverse needs and perspectives, and wider contexts and environments for which we have a responsibility as participants. Although the criteria for success in a CSLS would be collectively defined, from my perspective, such changes in thinking would be fitting for the development of EDIA and curricula design in an institutional setting.

Following up with action

I was asked to present my inquiry findings to the OU EDIA department, and as part of the enactment of activities towards the formation of a learning system, it will be valuable to share what I have learnt. Although the sample size of my research and co-inquiry was small, the feedback still seemed significant in light of the goals of OU curriculum designers and the actual experiences of students. I believe that through facilitation of critical learning, and well-designed feedback systems, more opportunity for inclusion could be offered to community subsystems.

As an individual, I will continue to:

Develop collaborative relationships across disciplines and communities

Help to create an atmosphere of openness and acceptance to multiple realities different from my own

Advocate for marginalised voices

Promote systemic learning and change

Help to normalise systemically desirable behaviour and language use

Share my feelings and feedback to those in positions of power

Empower others to do so the same.

Regarding methodology, there are problems with systemic inquiry in general, and not enough research on its effectiveness, especially as a means for addressing equity gaps as in my SoC (Sidman-Taveau and Hoffman, 2019, p. 135). I summarised the views of TB872 students on the opportunities and constraints of systemic inquiries, compiled into thematic areas of concern, along with possible compensations that I would recommend for the creation of suitable circumstances for systems practice (Table 2).

Table 2: Concerns regarding adoption and implementation of Systemic Inquiry (SI), and possible compensations for constraints (Adapted from TMA 02)

|

Area of Concern |

Possible Compensations |

|

Utilising Systems methodology for praxis |

- Adapt presentation of SI based on relevance and competence of practitioners - Express benefits of SI over (or in conjunction with) existing methods of practice |

|

Developing a system for learning in organisational contexts |

- Seek out relevant frameworks for SI that provide more structure if needed - Adapt SI to the limitations of the context - Adaptation of organisation to support SI, over the long term |

|

Operating in a culture of inclusivity |

- Collective development of inclusive practice over time - Dismantling of hierarchical systems of operation, in favour of collectivism |

I would like to learn more about how institutions can be incentivised to act for systemic benefit. For my own development and the development of the systems in which I practice, I am considering combining my knowledge and skills to design supporting materials that help practitioners apply Systems tools in social learning contexts.

Critical Evaluation

Being

My history sensitises me to issues of injustice, making me more likely to notice and frame situations like my SoC as problematic (Magombe, A., 2025, 4 January). I had to challenge my perceptions without dismissing the possibility of real systemic disempowerment. My design turn changed my perception of having no power to enact change (Magombe, A., 2025, 24 January).

Engaging

My understanding of Systems frameworks and methods, and their interdependence has grown (Magombe, A., 2025, 4 January). Diagramming has had huge implications for how I engage with systems, and expanded my repertoire as a graphic designer (Magombe, A., 2025, 1 February).

Figure 8: My transformed perception of my trajectory

Contextualising

Appreciation of STiP in development of my learning contract for S1

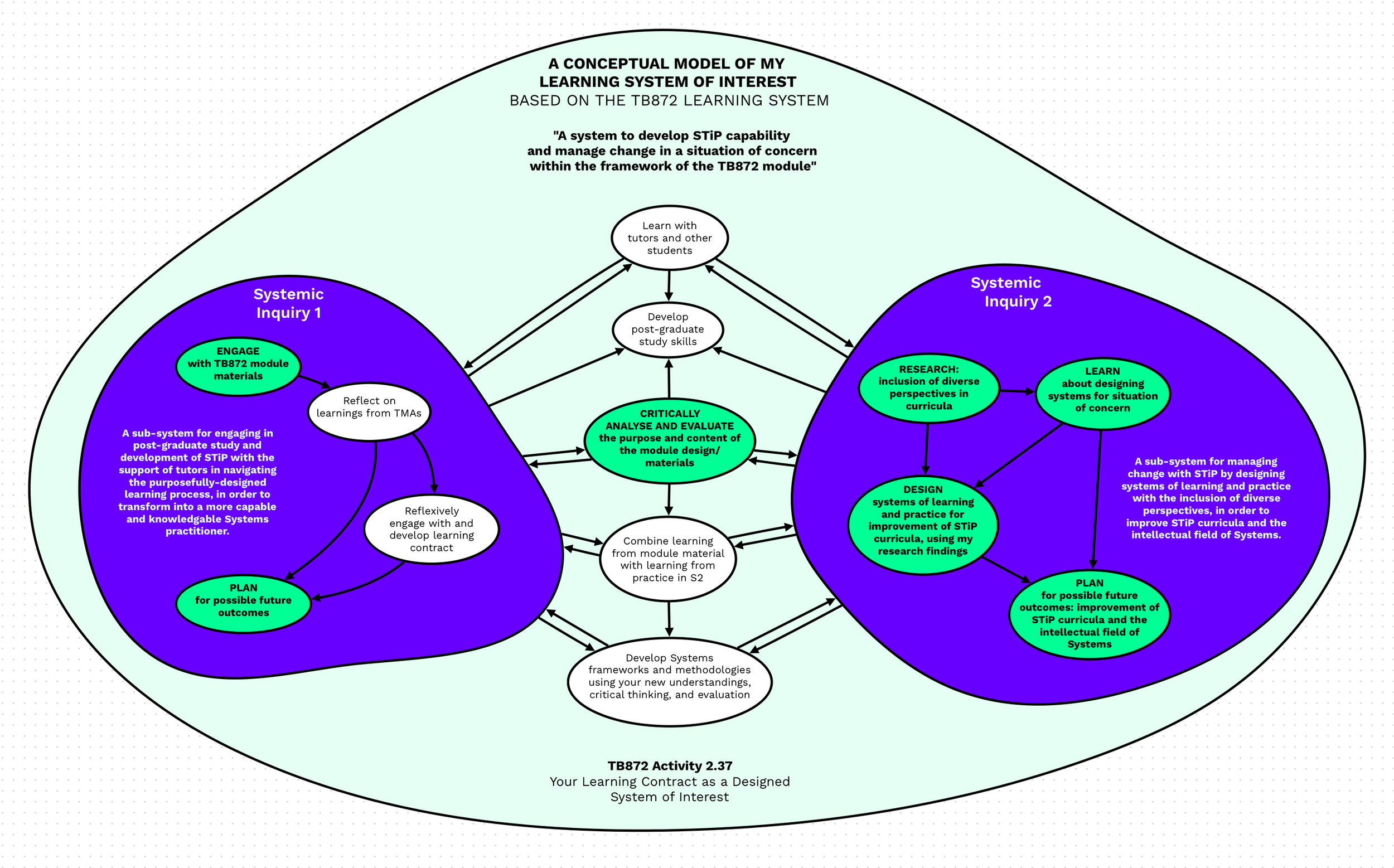

Developing my learning contract (Magombe, A., 2024, 29 November) helped me engage with, review and manage my performance in my S1 inquiry (developing STiP capability through study of TB872). In week 10 (Magombe, A., 2025, 10 January), I contextualised my priorities to the End-of-Module Assessment. Expanding relational awareness of the ‘learning system’, I realised I was ‘managing’. My thinking and practice were becoming more systemic. By week 13 (Magombe, A., 2025, 1 February), my braided inquiries were confusing. A conceptual model (Figure 9) helped to visualise and clarify my systemic understanding of TB872 processes (useful for S1 and S2), and was good practise in designing a conceptual activity model for a learning system.

Appreciation of social learning in development of a learning system for S2

Through the lineage of thinkers that influenced the design of TB872, I have emerged as a Systems practitioner. My learning system design is directly influenced by the TB872 system I enacted.

Stakeholders’ perspectives reframed and broadened my understanding of the impact of EDIA at the OU, and potentially ‘what ought to be’ (Ison, 2017, p. 164). I took their concerns on board when designing my learning system as that is what I hope will happen with future iterations as further inquiry is conducted.

Figure 9: A conceptual model of my learning system of interest v2 (referenced from TMA 02)

Managing

My learning contract as a conceptual model was useful for comparing logical processes that could fulfil the system purpose to real-world processes, providing a measure of performance (Checkland and Scholes, 1999). I enacted all of the activities.

I feel satisfied about progress in ‘closing the loop’ created by my emotional need to address a perceived problematic situation. These feelings are a measure of performance (Ison, 2017, p337). However, there are of course areas where I could improve in terms of the 3Es (Checkland and Poulter, 2006) and my understanding of Systems. This performance can be socially-determined against the suprasystem’s marking criteria—I look forward to the feedback!

‘A system to develop STiP capability and manage change in a situation of concern within the framework of the TB872 module’

Figure 10: A conceptual model of my learning system of interest v1 (referenced from TB872 TMA 02)

Summary & Conclusions

My situation of concern relates to EDIA at the OU. Stakeholders agreed that the situation is problematic and messy, and seemed keen to share their varied experiences to make improvements.

By engaging in ‘braided’ reflexive learning, and systemic (co-)inquiries for TB872, I experienced a ‘design turn’. Inspired by TB872, I wanted to emulate this process in order to understand and evaluate it. I contextualised SSM and CLS processes to my understanding of the situation in order to design a system for learning and managing change in my SoC.

The emphasis on reflexivity in my chosen approach is appropriate for challenging biases that impact implementation of EDIA; the social learning aspect crucial for including diverse perspectives in development of systemically desirable outcomes and processes.

My proposal for managing change in my SoC was designed based on information I learnt from my systemic inquiries—discussions with stakeholders about their experiences of EDIA at the OU, academic papers outlining the STiP praxis of Systems module designers at the OU, evaluations of OU EDIA practice, and my understanding of managing change with STiP as learnt from my study of the OU STiP module TB872.

My S2 inquiry revealed the power of individual reflexivity and social learning; it is feasible to enact if stakeholders can collaborate. In my case, student forums and chat groups were helpful but inefficient for collaboration. Self-organisation and self-transformation may be challenging without institutional facilitation of social learning and iterative change.

I question the ability of institutions to embrace democratic processes for managing change. We need institutional cultures that value purposeful inclusion, embrace uncertainty and are appreciative of complexity.

References

Anonymous (2025) OU Black STEM Whatsapp group message, 16 January.

Bawden, R. (2002) ‘Learning from the Future: Of Systems, Scenarios and Strategies Workbook’, in. Available at: https://www.semanticscholar.org/paper/Learning-from-the-Future-%3A-Of-Systems-%2C-Scenarios-Bawden/ad04fb62c794e3501dcb1f478bfec328d3462460#cited-papers (Accessed: 17 March 2025).

Blackmore, C. (ed.) (2010) Social Learning Systems and Communities of Practice. London: Springer London. Available at: https://doi.org/10.1007/978-1-84996-133-2.

Checkland, P. and Poulter, J.D. (2006) Learning for action: a short definitive account of soft systems methodology and its use for practitioner, teachers, and students. Chichester: Wiley.

Checkland, P. and Scholes, J. (1999) Soft systems methodology: a 30-year retrospective; and, Systems thinking, systems practice. [New ed.]. Wiley. Available at: https://cir.nii.ac.jp/crid/1130282268952033152 (Accessed: 20 December 2024).

Hartley, L. (2025) Email with A. Magombe, 28 January.

Ison, R. (2001) ‘Systems practice at the United Kingdom’s Open University’, in J. Wilby and G. Ragsdell (eds). Kluwer Academic, pp. 45–54. Available at: http://www.springer.com/uk/home/computer/programming?SGWID=3-40007-22-33335913-detailsPage=ppmmedia|aboutThisBook|aboutThisBook (Accessed: 19 January 2025).

Ison, R. (2017) Systems Practice: How to Act (2017). London: Springer London. Available at: https://doi.org/10.1007/978-1-4471-7351-9.

Ison, R. (2020) ‘Part 2. A systemic inquiry into systems thinking in practice’, TB872: Managing change with systems thinking in practice. Available at: https://learn2.open.ac.uk/mod/oucontent/view.php?id=2303521.

Ison, R. and Blackmore, C. (2012) ‘Designing and developing a reflexive learning system for managing systemic change in a climate-change world based on cyber-systemic understandings’, in. European Meeting on Cybernetics and Systems Research (EMCSR 2012), Vienna. Available at: http://www.emcsr.net/wp-content/uploads/2012/Book_of_Abstracts_EMCSR_2012.pdf (Accessed: 28 February 2025).

Ison, R. and Blackmore, C. (2014) ‘Designing and developing a reflexive learning system for managing systemic change.’, Systems, 2(2), pp. 119–136. Available at: http://www.mdpi.com/2079-8954/2/2/119/htm (Accessed: 20 December 2024).

Ison, R. and Blackmore, C. (2020) ‘Part 1. Creating the starting conditions for your systemic inquiries’, TB872: Managing change with systems thinking in practice. Available at: https://learn2.open.ac.uk/mod/oucontent/view.php?id=2303519.

Ison, R. and Blackmore, C. (2020) TB872 Box 2.9 Taking a design turn in your STiP, The Open University. Available at: https://learn2.open.ac.uk/mod/oucontent/view.php?id=2303521§ion=2.5.1 (Accessed: 9 April 2025).

Ison, R., Blackmore, C. and Armson, R. (2007) ‘Learning Participation as Systems Practice’, The Journal of Agricultural Education and Extension, 13(3), pp. 209–225. Available at: https://doi.org/10.1080/13892240701427599.

Ison, R., Grant, A. and Bawden, R. (2014) ‘Scenario Praxis for Systemic Governance: A Critical Framework’, Environment and Planning C: Government and Policy, 32(4), pp. 623–640. Available at: https://doi.org/10.1068/c11327.

Kitchener, K.S. (1983) ‘Cognition, Metacognition, and Epistemic Cognition: A Three-Level Model of Cognitive Processing’, Human Development, 26(4), pp. 222–232. Available at: https://doi.org/10.1159/000272885.

Lemonius, R. (2025a) Email with A. Magombe, 28 January.

Lemonius, R. (2025b) Video call with A. Magombe, 28 January.

Lotz, N. (2025) Email with A. Magombe, 13 February.

Magombe, A. (2024) ‘Exploring Social Learning Systems – TB872 Pt 01 Wk 04’, AlexMakes, 29 November. Available at: https://web.archive.org/web/20241206032646/https://www.alexmakes.co/2024/11/29/exploring-social-learning-systems-tb872-pt-01-wk-04/ (Accessed: 21 April 2025).

Magombe, A. (2025a) ‘Framing in Systemic Inquiries with the Juggler – TB872 Part 02 Week 11-12’, AlexMakes, 24 January. Available at: https://web.archive.org/web/20250208155010/https://www.alexmakes.co/2025/01/24/framing-in-systemic-inquiries-with-the-juggler-tb872-part-02-week-11-12/ (Accessed: 21 April 2025).

Magombe, A. (2025b) ‘Relational Dynamics, Values and Worldview Clashes - Systems Practice - TB872 Part 2 Week 8-9’, AlexMakes, 4 January. Available at: https://web.archive.org/web/20250119052410/https://www.alexmakes.co/2025/01/04/relational-dynamics-values-and-worldview-clashes-exploring-systems-practice-tb872-part-2-week-8-9/ (Accessed: 21 April 2025).

Magombe, A. (2025c) ‘Systemic Inquiry towards a Learning System of Interest – TB872 Part 02 Week 13’, AlexMakes, 1 February. Available at: https://web.archive.org/web/20250208152212/https://www.alexmakes.co/2025/02/01/systemic-inquiry-towards-a-learning-system-of-interest-tb872-part-02-week-13/ (Accessed: 21 April 2025).

Magombe, A. (2025d) ‘Systems Practice: Being, Engaging, Contextualising, Managing – TB872 Part 2 Week 10’, AlexMakes, 10 January. Available at: https://web.archive.org/web/20250119052022/https://www.alexmakes.co/2025/01/10/systems-practice-being-engaging-contextualising-managing-tb872-part-2-week-10/ (Accessed: 21 April 2025).

Magombe, A. et al. (2025) ‘Your experience of Systems and EDIA at the OU (my situation of concern)’, TB872 Module Discussion. Available at: https://learn2.open.ac.uk/mod/forumng/discuss.php?d=4957429 (Accessed: 17 March 2025).

Maiteny, P.T. and Ison, R.L. (2000) ‘Appreciating systems: critical reflections on the changing nature of systems as a discipline in a systems-learning society’, Systemic Practice and Action Research, 13(4), pp. 559–586. Available at: https://oro.open.ac.uk/173/ (Accessed: 19 January 2025).

Ramage, M. and Blackmore, C. (2020) ‘Part 3. Social learning systems for managing change’, TB872: Managing change with systems thinking in practice. Available at: https://learn2.open.ac.uk/mod/oucontent/view.php?id=2303527.

Sidman-Taveau, R. and Hoffman, M. (2019) ‘Making Change for Equity: An Inquiry-Based Professional Learning Initiative’, Community college journal of research and practice, 43(2), pp. 122–145. Available at: https://doi.org/10.1080/10668926.2018.1424665.

The Open University (2020a) 2.2 The Module Map, TB872 Module Guide. Available at: https://learn2.open.ac.uk/mod/oucontent/view.php?id=2303551§ion=2.2 (Accessed: 21 April 2025).

The Open University (2020b) 3.3.4 Bawden: critical social learning systems, TB872. Available at: https://learn2.open.ac.uk/mod/oucontent/view.php?id=2303527§ion=3.3.4 (Accessed: 21 April 2025).

The Open University (2022) ‘Equality Scheme 2022-2026’.

The Open University (2023a) Institutional EDI Plan. Available at: https://university.open.ac.uk/equality-diversity/content/equality-scheme-objectives (Accessed: 27 February 2025).

The Open University (2023b) ‘V1.0 Process Mapping as of 13.9.23’.

The Open University (2024a) ‘Access and Participation Plan 2025-26 V1’. Available at: https://university.open.ac.uk/widening-participation/aps-england-access-and-participation-plan.

The Open University (2024b) ‘Guidance Notes for Users V6.1 as of 7.10.24 with navigation’.

The Open University (2024c) ‘ICT template V6.1 as of 7.10.24’.

The Open University (2024d) ‘ICT V6 DESIGN_prompts posters’.

The Open University (2024e) ‘ICT V6 Training Resource V1.0 published June 2024’.

Veuger, S.J. et al. (2023) ‘Inclusive Frameworks in Online STEM Teaching and Learning’, in J. Keengwe (ed.) Handbook of Research on Innovative Frameworks and Inclusive Models for Online Learning. IGI Global, pp. 28–51. Available at: https://oro.open.ac.uk/92330/ (Accessed: 27 February 2025).