A Systemic Approach to Making Strategy for Improvement of Wellbeing

TB871: Making Strategy with Systems Thinking in Practice - The Open University

Project Report: “A Systemic Approach to Making Strategy for Improvement of Student Wellbeing at The Open University” (2025)

Abstract

As part of my study of Systems Thinking in Practice (STiP) on the TB871 module at The Open University (OU), I iterated between theoretical learning and practical use of five systems approaches—System Dynamics (SD), Viable System Model (VSM), Strategic Options Development and Analysis (SODA), Soft Systems Methodology (SSM) and Critical Systems Heuristics (CSH)—to develop my systems practice capability. I evaluated the effectiveness of each tool for engaging with aspects of STiP—understanding interrelationships (uIR), engaging with multiple perspectives (eMP), and reflecting on boundary judgements (rBJ). This allowed me to select appropriate tools for further inquiry towards the design of a systemic process for improving a situation of interest. I categorise my initial explorations and findings through TB871 as Systemic Inquiry 1 (SI1), and the iterative developments for this report as Systemic Inquiry 2 (SI2).

I am personally invested in the area of practice (AoP) relating to managing student wellbeing at the OU, and I have focused on situations within that AoP to experiment with the five systems tools in making strategies for improvement. The OU has stated that a strategic move towards a systemic approach to student wellbeing is needed, and this is supported by advisory organisations such as Universities UK (The Open University, 2020; Universities UK, 2023). However, the application of specific systems approaches appears to be lacking.

I used SSM and CSH to learn about the situation of interest, critique my thinking and processes, and design a model of purposeful activity to improve the situation. I lacked capacity to engage with multiple perspectives in ongoing discourse which limited my learning in terms of uIR and rBJ. I therefore recommend action that involves stakeholders in using STiP to collectively learn about the situation and, through their practice, develop STiP capability over time—essentially, I recommend the purposeful development of inclusive, critical learning systems. In this report, I embed critical systems practice and development of STiP capability and competence in a proposed conceptual activity model, use CSH to identify leverage points for ethical and inclusive change, and discuss the potential limitations and opportunities of the selected approach.

Introduction

As a student at OU that has health issues and professional experience in Education, I am interested in the AoP relating to managing student wellbeing at the OU. ‘Wellbeing’ is broad, complex, sensitive to change and heavily impactful at the level of the individual and their communities. Many sectors, entities and individuals interact to improve student wellbeing (e.g. students, tutors, support staff, OU leadership, external services), contributing to the complexity of situations in this AoP. Mental health, which is used almost interchangeably with wellbeing throughout many of the cited sources, is shown to greatly impact learning and overall performance, likelihood of underachieving or withdrawing from education (Universities UK, 2023). Change over time adds to uncertainty, with mental health potentially declining if not addressed (Hughes and Spanner, 2019). Additionally, distance learning provides its own unique stressors (Stone and O’Shea, 2019). Mental health of university students is an increasing issue (Hughes and Spanner, 2019; The Open University, 2020) and universities have a duty of care to students by law (Office for Students, 2024).

The Open University (2025) ‘Access and Participation Plan’ (APP) states an intention to adopt a systemic approach, ‘working across functional ‘boundaries’ to address barriers to student success and equity of outcome’. This is in line with the ‘whole university’ approach promoted in the Stepchange mentally healthy universities model that informs institutional strategy across four areas: learn, support, work, live (The Open University, 2020; Universities UK, 2023). The APP and institutional wellbeing strategies generally appear to be well-informed, carefully considered and designed for practical application. However, in discussion with Nicole Lotz (2025), Deputy Director of STEM EDIA at the OU (Lotz, 2025), no specific systems experts have been consulted in the development of the OU strategy.

This report outlines some of the ways in which my learning throughout TB871 and its TMAs, which I will refer to as SI1, informed my process for designing a system to improve a situation of interest in my AoP (referred to as SI2).

My goals for SI1 and SI2 have been to:

Gain understanding of the situation of interest with consideration of limitations

Maintain a critically reflective mindset

Develop STiP capability by using the available information and resources creatively to make strategy with STiP

Make strategy towards systemically desirable, culturally feasible and ethically defensible change.

Figure 1: A system to demonstrate ability to make strategy in a situation of interest using STiP

Systemic Inquiry 1:

Informing methodological selectivity

In my design of a system for the improvement of my situation of interest, I considered the factors that are necessary for effective STiP such as those outlined in the STiP heuristic (Reynolds et al., 2020, 1.3.3), and aspects that had given me trouble in my own inquiries. In SI1, I used SSM to define a system of interest for the exploration and improvement of a problematic situation. Using SSM Analyses 1-3 and CATWOE aided my thinking about interrelationships, but later use of CSH provided further critique on the reference system underlying my definition and prompted me to identify emancipatory, accommodating actions for improvement—crucial for systemically desirable and culturally feasible change.

Facilitating critical learning in a situation of interest

Due to my lack of access to stakeholders for critical discourse, and my limitations as a practitioner, my ultimate recommendation would be an activity model of a critical learning system—a transitional object that facilitates the various levels of social learning alongside the changing situation. The ‘transformation’ not only supports the making of strategy for desirable and feasible change, but potentially the formation of purposeful Critical Social Learning Systems (as described by Bawden in Blackmore, 2010, pp. 39-56, 89-101) that develop competence and capability over time for improved enactment of STiP beyond any initial recommendations for improvement. As such, my situation of interest for SI2 relates to my current concerns regarding the improvement of student wellbeing at the OU through the design and enactment of a critical learning system.

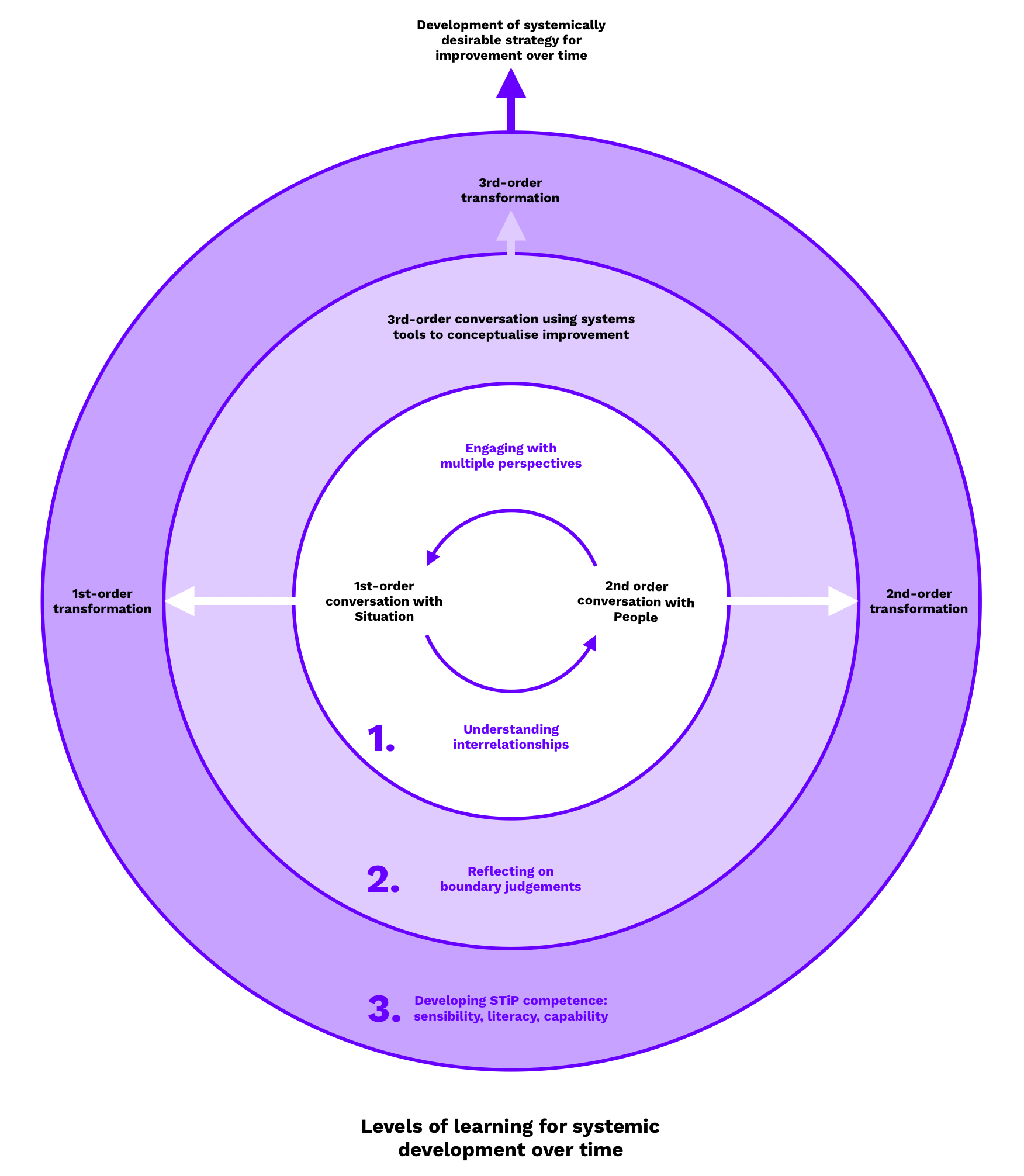

The capability of the individual and their community to engage in critical reflection can open up the possibility for systemically desirable change (see Figure 2) and is therefore a priority in my own practice and in my recommendations for others. This is supported by development of certain skills, and attributes underpinned by capacity for critical reflection (Reynolds et al., 2020, P6.3.3; Reynolds et al., 2020, P6.4.2).

Systematic application of tools such as CSH supports critical reflection in the form of boundary critique, and other aspects of STiP (engaging with different perspectives or ‘reference systems’, and understanding interrelationships) until relevant skills are adopted as regular practice. Additionally, compared to approaches like SODA, CSH is more accessible and does not require professional facilitation to be effective in a variety, and can be adapted to accommodate individual differences (Marrington et al., 2020). Both CSH and SSM provide an adaptable, organised process of inquiry that may be beneficial to the development of organisational and individual STiP capabilities over time.

I personally enjoyed using SSM as a systematic process for defining the boundaries of a system of interest to explore, and for designing activity models so that is what I have chosen for modelling my recommended learning system for stakeholders to undertake.

Figure 2: Levels of learning for systemic development over time

Systemic Inquiry 2:

Application of SSM & CSH

A system to develop a critical learning system to improve student wellbeing at the OU through systemically desirable, culturally feasible and ethically defensible change (Figure 3).

During SI1 and SI2, my understanding of the situation deepened as I researched perspectives such as those expressed by Hughes and Spanner, 2019; Stone & O’Shea, 2019; The Open University, 2020, 2025; Worsley et al., 2020; Universities UK, 2023; Lister et al., 2024; Office for Students, 2024. I critiqued my understanding through boundary reflection using CSH questions (see Appendix A) which allowed me to identify potential leverage points and make specific recommendations for strategic action to improve the situation of interest.

Figure 3: A system to develop a learning system to improve student wellbeing at the OU (v1)

Strategic recommendations

Recommendations from CSH boundary critique

(See Appendix A for CSH Q&A)

Motivation

Co-inquiry into interventions to accommodate all stakeholders

Preventative, culturally influential action to remove systemic barriers

Adapt existing systems for monitoring and evaluating performance to inform and support collective decision-making

Institutional support for localised strategic change by stakeholder groups or representatives, allowing speedier experimentation and development cycles.

Control

Transparency of resource management, building trust and accountability

Collaboration with external health and social services to balance pressures on institutions

Purposefully employ and collaborate with people representative of student and staff interests

Provide resources to student and staff representatives such as unions and support groups to enact localised change.

Expertise

Support stakeholders to utilise existing research capacity and form communities of practice rather than relying on individual ‘experts’

Increase feasibility of transition to more democratic processes of decision-making by merging traditional management with systemic inquiry and design processes

Adapt existing technological infrastructure to simplify and promote community engagement

More clarity regarding reasoning for strategy, sources of information and expertise, to maintain transparency and accountability.

Legitimacy

Develop individual and collective STiP literacy, sensibility, capability

Embed STiP in strategy, policy, curricula, and staff training

Standardise learning and adaptability in the design of institutional processes and interventions

Continue building stakeholder relationships

Show initiative and innovation in institutional co-creation, and inclusive practice

Explore options collaboratively to accommodate a variety of needs

Clarify how different worldviews are accommodated, and the weight different worldviews have in the development of strategy

Promote visibility of support communities, unions and representatives for students and staff.

Specific to ongoing development of the learning system:

Utilise existing technological systems, but be aware of new technologies that could improve processes

Develop accessible systems for co-inquiry and ongoing communication, promoting collaborative relationships amongst stakeholders

Automate transparency of feedback and development, showing how different worldviews are used to make improvements

Embed STiP, learning, and adaptation in all processes to support long-term STiP development.

Defining the system of interest

Following boundary critique and my learning from SI1, I feel that my PQR statement is appropriate and would support the wider system for student wellbeing (see Figure 4):

A system to develop a critical learning system to improve student wellbeing at the OU through systemically desirable, culturally feasible and ethically defensible change.

Figure 4: A system to develop a systemic approach to making strategy to fulfill the purpose of a system to support student wellbeing

As a root definition:

Decision-makers: A system for OU stakeholders to collectively develop a systemic approach to making strategy for improvement of wellbeing... (SSM Analysis 1, CSHq4, ‘control’)

Worldview: ...in the belief that STiP supports the making of strategy that is systemically desirable, culturally feasible and ethically defensible... (PQR, CSHq12, ‘legitimacy’, The Open University, 2020; Universities UK, 2023)

Transformation: ...transforming management and strategy-making processes from a target-based approach to a systemic approach through the development of STiP over time... (PQR, CSHq2, ‘motivation’; Ison, 2017a, pp. 223-250)

Those affected: ...primarily focussing on the wellbeing of students, but with consideration of all stakeholders affected, including teaching and support staff, and local health and social care services that may be adversely affected by changes... (SSM Analysis 1, CSHq1, CSHq10, ‘motivation’, ‘legitimacy’)

Actors: ...as all stakeholders participate in making strategy that is systemically desirable, including expertise on systems thinking and group workshop facilitation, teaching and learning, wellbeing and mental health, institutional structures, functions, resources, roles, and capacity to enact change at various levels... (CSHq7, ‘expertise’)

Environmental constraints: ...with consideration of environmental constraints such as legal and ethical guidelines, cultural support, consumer choice, capacity of services and interventions to meet stakeholder needs (CSHq6, ‘control’).

A model for action

I outline the logical steps needed to enact the learning system, and include tool recommendations that are appropriate in social learning settings:

Define performance measures

Analyse aspects of situation as defined by CATWOE or CSH questions

Evaluate impact of current processes for making strategy regarding wellbeing interventions

SODA workshops to discuss perceived issues and strategic options

SD CLD to identify causal relationships

CSH questions to review ethical / political issues

VSM to review viability of system

Identify leverage points for strategic action to improve processes

SODA analyses to identify ‘potent’ options for next actions

SD CLD to identify problematic influences

VSM to identify how requisite variety can be met

VSM to identify where necessary system functions are not being fulfilled

CSH questions to evaluate the reference systems underlying strategic recommendations

Embed STiP in strategy, activity, and assets to facilitate 1st, 2nd and 3rd order conversation

SSM to design activity systems

Use STiP to evaluate impact of wellbeing interventions

SODA workshops to discuss perceived issues and strategic options

Use STiP to plan wellbeing interventions

SSM to design activity system

VSM to design viable recursive systems

CSH questions to ensure accommodation of various stakeholders

Enact interventions

Monitor and evaluate

VSM to review viability of system

SSM(p) to evaluate and redesign process

STiP heuristic to evaluate process in regard to effectiveness of enacting and developing STiP

Take control action

These steps can be seen as points to discuss emergent outcomes and cumulative learning from the learning cycle (Figure 5).

Figure 5: A conceptual activity model of a system for OU stakeholders to collectively develop a systemic approach to making strategy for improvement of student wellbeing

I have focused on a level of activity currently most accessible to individuals in OU leadership and management to collaborate on. However, with the introduction of purposeful activities that utilise STiP tools, I believe that (like in my own inquiries) the importance of eMP, uIR and rBJ will become apparent. There will undoubtedly be challenges in enacting desirable and feasible change within the existing institutional structure, but there is a greater chance of finding where barriers and opportunities to change are when the combined knowledge of all stakeholders is utilised. Embedding monitoring and evaluation as a key part of the inquiry process should help to develop STiP capability and competence over time (Ulrich and Reynolds, 2020 in Reynolds and Holwell, 2020, pp. 295-7), improving capacity to make systemically desirable change (Bawden in Blackmore, 2010, pp. 39-56, 89-101; Ison et al., 2014, pp. 623-640).

The steps may be introduced transitionally as a systematic process, whilst developing capacity for iteration—it would require suitable resources, including sufficient time for stakeholders to collaborate. For efficiency, stakeholder discussions at each stage of the process can be structured by asking questions about activities in the model, and their dependencies (Checkland and Poulter, 2006, p. 52, Figure 2.12).

Performance measures can be defined from aspects of the situation referenced by CATWOE or CSH questions. Examples of performance measures to consider include:

Efficacy: Does the system support both the development of interventions to improve student wellbeing, and improvement of organisational practice? Are processes accessible, accommodating stakeholders’ individual differences, preferences, perspectives, and practices?

Efficiency: What are systemic barriers to the improvement of student wellbeing, and to the systemic process of making strategy? Are monitoring and evaluation processes providing enough relevant information for making strategy with STiP?

Effectiveness: Are all stakeholders able to participate in making strategy using STiP? Are all viewpoints given equal value? To what extent is wellbeing improved across all demographics of students and staff?

Figure 6: A system to develop a learning system to improve student wellbeing at the OU (v2)

Evaluating SI2 methodology

Although the specific tools I select may vary depending on the situation of interest, my methodology of designing a system of learning would be appropriate for any complex situation. For the purposes of this report, I reflect on my use of systems tools and approaches as a means of developing my STiP and potentially improving the situation of interest.

Making strategy

I refined my method for SI2 (see Figure 3 and 6) during the process of describing it in this report and realising that certain activities such as the SSM analyses were not as relevant as the CSH questions for this particular inquiry. The method could be refined further to be more efficient in similar use cases, but I found it useful nonetheless as it helped me to explore my situation of interest and develop my STiP within the current limitations of my practice. The systematic process simplified what can be a confusing process for inexperienced practitioners such as myself (Asby et al., 2020, 5.2.1; Checkland and Poulter in Reynolds and Holwell, 2020, p. 206, 223-4, 226; Reynolds et al., 2020, 6.2.1, 6.2.3).

To evaluate my recommendations, I have assessed the strategy in relation to the defined system of interest and have found that the main aspects are addressed in the activity diagram and the recommendations resulting from CSH boundary critique. I found combining SSM and CSH to be reasonably accessible with some adjustments such as rephrasing of CSH questions.

uIR, eMP, rBJ

I have found that eMP, supported by rBJ, is how a ‘bigger picture’ of a situation is gained. I was therefore limited in my understanding of interrelationships as they may be conveyed from different stakeholder perspectives. CSH questions provided insight through ‘1st order conversation’ on how different aspects of the situation are related and may impact different stakeholder groups (Reynolds et al., 2020, 6.1.3, 6.2.7, 6.4.3). If I had more time to iterate the process using the resources available to me at the moment, I could explore further hypothetical perspectives or design more alternative reference systems using information from OU reports or academic research about the institution as I have done in my inquiries so far.

Ideally, greater input from stakeholders could help to develop understanding of both the structural interrelationships, that can be explored through approaches such as System Dynamics (SD) or Viable System Model (VSM), and the soft system aspects through SSM and CSH. SODA workshops with an experienced facilitator would be valuable for gaining critical input from stakeholders, identifying potent options for strategic change, and shifting the boundaries of systems of interest in order to accommodate others (Reynolds et al., 2020, Block 4).

The presentation of proposed strategy would need to be made more accessible to people of varying levels of understanding and different ways of working. Simplified language, or supporting information may be used to facilitate productive encounters. With existing practices and infrastructure, statistical data, consultations and questionnaire feedback can be utilised to make strategy with STiP.

Avoiding thinking traps

I found that purposefully utilising systems tools mitigated reductionism and dogmatism (Reynolds et al., 2020, 1.3.2, 6.2.1). For example, SSM and CSH helped me to avoid reductionist thinking through critical reflection, as the process of defining the system of interest and thinking through associated activities revealed the necessity of social learning in the making of desirable, feasible strategy. The direct prompts to consider different aspects of the situation helped me to understand interrelationships in the situation and thus be more holistic. However, my opportunities for second-order conversations, and therefore pluralistic practice, was lacking and potentially creating a risk of dogmatic thinking. I do think that SSM and CSH combined provide several opportunities to reflect on boundary judgements, mitigating some of the concerns I have about my own potential biases and projection whilst making strategy. I really appreciated the systematic processes of my chosen approaches for critical reflection, and development of my STiP capability.

Practitioner Statement

Learning about myself and others

My inexperience as a systems thinking practitioner brings with it a humility that serves me well as a student—openness to critique and emergence supports effective systems thinking. However, lack of confidence drives me to seek comfort in systematic thinking. During the inquiries described in this report, I enjoyed the systematic approach that could be taken with CSH and SSM. However, this does not reflect ‘a certain dash, a light-footedness, a deft charm’ that characterises the mature, internalised, non-linear STiP that comes with experience (Checkland and Scholes, 1990, p. 302). Perhaps my confident experimentation with modelling and creative application of systems tools conveys ‘a certain dash’, and my reflectiveness about my assumptions shows potential for ‘light-footedness’ in complex situations. Gaining experience in working directly with others in the ‘mess’ and persistently challenging my discomfort with ambiguity may help me to have more ‘grace under pressure’ and flexibility in my practice (Checkland and Poulter, 2006, p. 169).

I have already found myself being more empathetic to very different worldviews and thinking more holistically as a result of using systems tools in TB871. Reflecting on my judgements can feel uncomfortable as I reveal my own ‘thinking errors’ and contradictions between my self-perception and inevitable partiality. However, finding greater acceptance of others’ and my own ‘flaws’ brings some relief and hope. Developing STiP capability through praxis is transformative (see Figure 7), changing perception of situations, influencing our choices and interpretations of outcomes, and shaping the environment through emergence (Ison, 2017b; Shah et al., 2020, P5.1.4). This is why the development of my own learning through SI1 directly inspired the design of the learning system for improving the situation of interest—my own STiP opened me up to greater possibilities of change, and I would like to share this experience with others.

Figure 7: 1st-, 2nd- and 3rd-order conversation and transformation through engagement with STiP

Learning about tools and the situation

To make strategy in my situation of interest, I had to get an understanding of the situation, using systems approaches for uIR, eMP, and rBJ (Reynolds et al., 2020, 1.3.3). Critical reflection was particularly important given my limitations with eMP, as I had to interpret my own and others’ value judgements and factual judgements about the situation without critical or clarifying feedback.

SSM and CSH met my criteria well and gave me better insight into how the situation can be improved in a way that is desirable and feasible. CSH exposed the partiality of different ways of framing the situation, surfacing ethical questions about whose wellbeing is prioritised, and gave me language to express the limitations of my judgements and engage with alternatives. My iterations of conceptual activity models led me to the design of a learning system that builds upon collective knowledge which I then believed would be the ideal option for systemically desirable strategy.

Communicating about systems

It was challenging to communicate my process—there was a lot that was changed or discarded to fit into the scope of the report. I have attempted to balance the ‘mess’ with clarity of communication about the more useful and relevant aspects of my learning experience. With more experience, I will be more adept and efficient in my choices of approach, and communication of my processes.

Conclusion

Experimenting with different tools expanded my toolbox, giving me options to pull from when dealing with different situations. For example, I recognise the strengths of ‘hard’ systems approaches like SD and VSM for understanding, evaluating, and designing system structures. ‘Soft’ systems tools, including SODA, SSM, and CSH have given me confidence to accept and make sense of the complexity of human existence, as well as broaden my own worldview. I have learnt that learning is the key, as a practitioner, as a stakeholder, as an advocate for change—I cannot be ethical, inclusive, and confident in my decision-making without first being humble, hearing others, and questioning my assumptions. I am driven to continue learning, so that I can have skills and experience to contribute when I am able to facilitate change alongside others, and be able to learn from those experiences too.

-

Asby, R. et al. (2020) TB871: Block 5 Tools stream, The Open University. Available at: https://learn2.open.ac.uk/mod/oucontent/view.php?id=2438604 (Accessed: 1 August 2025).

Bawden, R. (2010) ‘Messy Issues, Worldviews and Systemic Competencies’, in C. Blackmore (ed.) Social Learning Systems and Communities of Practice. London: Springer, pp. 89–101. Available at: https://doi.org/10.1007/978-1-84996-133-2_6.

Bawden, R. (2010) ‘The Community Challenge: The Learning Response’, in C. Blackmore (ed.) Social Learning Systems and Communities of Practice. London: Springer, pp. 39–56. Available at: https://doi.org/10.1007/978-1-84996-133-2_3.

Checkland, P. and Poulter, J.D. (2006) Learning for action: a short definitive account of soft systems methodology and its use for practitioner, teachers, and students. Chichester: Wiley, pp. 52, 169.

Checkland, P. and Poulter, J.D. (2020) in M. Reynolds and S. Holwell (eds) Systems Approaches to Making Change: A Practical Guide. London: Springer London, pp. 206, 223–224, 226. Available at: https://doi.org/10.1007/978-1-4471-7472-1.

Checkland, P. and Scholes, J. (1990) in Soft systems methodology in action. USA: John Wiley & Sons, Inc., p. 302.

Hughes, G. and Spanner, L. (2019) The University Mental Health Charter, Leeds: Student Minds. Available at: https://hub.studentminds.org.uk/university-mental-health-charter/ (Accessed: 27 May 2025).

Ison, R. (2017a) ‘Four Settings That Constrain Systems Practice’, in R. Ison (ed.) Systems Practice: How to Act: In situations of uncertainty and complexity in a climate-change world. London: Springer, pp. 223–250. Available at: https://doi.org/10.1007/978-1-4471-7351-9_9.

Ison, R. (2017b) Systems Practice: How to Act (2017). London: Springer London. Available at: https://doi.org/10.1007/978-1-4471-7351-9.

Ison, R., Grant, A. and Bawden, R. (2014) ‘Scenario Praxis for Systemic Governance: A Critical Framework’, Environment and Planning C: Government and Policy, 32(4), pp. 623–640. Available at: https://doi.org/10.1068/c11327.

Lotz, N. (2025) ‘Email with A. Magombe, 13 February.’

Marrington, P. et al. (2020) TB871: Block 4 People stream, The Open University. Available at: https://learn2.open.ac.uk/mod/oucontent/view.php?id=2438599 (Accessed: 22 July 2025).

Office for Students (2024) The Office for Students mental health analytics project, Jisc. Available at: https://beta.jisc.ac.uk/reports/the-office-for-students-mental-health-analytics-project (Accessed: 23 May 2025).

Reynolds, M. and Holwell, S. (eds) (2020) Systems Approaches to Making Change: A Practical Guide. London: Springer London. Available at: https://doi.org/10.1007/978-1-4471-7472-1.

Reynolds, M. and the module team (2020a) TB871: Block 1 Tools stream, The Open University. Available at: https://learn2.open.ac.uk/mod/oucontent/view.php?id=2438584 (Accessed: 20 May 2025).

Reynolds, M. and the module team (2020b) TB871: Block 6 Tools stream, The Open University. Available at: https://learn2.open.ac.uk/mod/oucontent/view.php?id=2438608&printable=1 (Accessed: 24 August 2025).

Shah, R., Walker, M., and the module team (2020) TB871: Block 5 People stream, The Open University. Available at: https://learn2.open.ac.uk/mod/oucontent/view.php?id=2438605 (Accessed: 18 August 2025).

Stone, C. and O’Shea, S. (2019) ‘Older, online and first: Recommendations for retention and success’, Australasian Journal of Educational Technology, 35(1). Available at: https://doi.org/10.14742/ajet.3913.

The Open University (2020) ‘Student and Staff Mental Health and Wellbeing Strategy 2020-2023: Promoting and institutional approach’. Available at: https://help.open.ac.uk/students/_data/documents/helpcentre/mental-health-wellbeing-strategy.pdf.

The Open University (2025) ‘Access and Participation Plan’. Available at: https://university.open.ac.uk/widening-participation/sites/www.open.ac.uk.widening-participation/files/files/The%20Open%20University_APP_2025-26_V1_10007773.pdf.

Universities UK (2023) Stepchange: mentally healthy universities. Available at: https://www.universitiesuk.ac.uk/what-we-do/policy-and-research/publications/stepchange-mentally-healthy-universities (Accessed: 23 May 2025).

Worsley, J., Pennington, A. and Corcoran, R. (2020) Student mental health interventions: state of the evidence. What Works Centre for Wellbeing. Available at: https://whatworkswellbeing.org/resources/student-mental-health-review-of-reviews/ (Accessed: 23 May 2025).

Appendix A:

CSH reference system

Normative mapping 'what ought to be' based on SI1 vs Value judgements and factual judgements on 'what is'

PQR:

A system to develop a critical learning system in order to improve student wellbeing at the OU by supporting a systemic approach of critical social learning and strategic design towards systemically desirable, culturally feasible and ethically defensible change.

-

[CSHq2] Purpose

Value judgements (‘What ought to be’):

To improve student wellbeing at the OU through systemically desirable, culturally feasible and ethically defensible change.

Factual judgements (‘What is’):

Increasing awareness and uptake of OU wellbeing services in order to reach institutional targets and meet advisory guidelines

Utilising expenditure effectively by targeting interventions at groups that have high awarding gaps

Improving student performance

Improving staff productivity

[CSHq1] Beneficiaries

Value judgements (‘What ought to be’):

Students are primary focus but, ideally, all stakeholders benefit from systemically desirable changes

Factual judgements (‘What is’):

OU leadership

Financial investors

Governing bodies

Some of the students using OU wellbeing services

[CSHq3] Measures of improvement

Value judgements (‘What ought to be’):

Critical learning system is sustainably iterative

Encompassing recursive systems remain functional or are improved

Increased student satisfaction, self-reports and assessments regarding improved individual wellbeing

Improved academic assessments and reduced awarding gaps

Improvements across all demographics of students and staff

Changes in wellbeing are ethically tracked and effectively acted upon in the provision of relevant support as needed

Factual judgements (‘What is’):

Statistical increase in use of wellbeing services

Positive feedback regarding experiences of using existing wellbeing services

Achieving monitoring and evaluation targets for improvement of outcomes for disadvantaged groups

Reduction in awarding gaps amongst disadvantaged groups

Increased student retention

Investor satisfaction

Boundary Critique

The hierarchical institutional structure, target-based operations, and capitalist economic context supports financially incentivised practice that benefits those with the most power in the hierarchy.

Qualitative feedback of individual experiences are likely to be overlooked in favour of collating institutional statistics into manageable data presentation for analysis.

Institutional targets can be seen as harmful to systemically desirable change, but they are also a practical and common way of understanding and managing complex systems.

The scale of operations will provide challenges to equitable representation of stakeholders.

Adaptation to change may be slow on an institutional level.

Prioritising the wellbeing of certain groups may make practical sense in short-term management of resources, but capability to meet the needs of all stakeholders may be reduced over time (Meadows, -).

-

[CSHq5] Resources

Value judgements (‘What ought to be’):

Structural

Suitable physical and digital environments for facilitation of social learning

Technological infrastructure that can support accessible, effective and ethical monitoring, efficient response to feedback, evaluation, communication, intervention and access to information

Sufficient finances for continual development of interventions, resources, environments and staff

Human

Culture of collective learning as part of development

Critical social learning system / communities of practice

Qualified staff trained in wellbeing support

Support and training for staff

Access to and collaboration with experts in wellbeing

Effective administration of institutional processes

Conceptual

Research and development for understanding and improvement of wellbeing interventions, and improvement of learning process

Standards for accessibility of design

Systems for recording and retrieving organisational learning

Factual judgements (‘What is’):

Budgets and funding

Staffing levels, allocation, and training

Curriculum design and adjustment

[CSHq4] Decision-makers

Value judgements (‘What ought to be’):

Governing agencies

OU leadership

Administrators

IT Systems staff

Department managers

Tutors

Support staff

Student representatives

Factual judgements (‘What is’):

OU leadership

EDIA / Student Support Teams

[CSHq6] Decision environment

Value judgements (‘What ought to be’):

Legal frameworks

Legal and financial advice supporting fulfillments of duty of care within legal guidelines

Independent inspection ensuring legal and ethical practice

External consultation reviewing and recommending wellbeing and mental health interventions

Cultural support towards wellbeing support and normalisation of help-seeking behaviour in wider society, academia and adjacent communities

Consumer choice—students’ decision to choose alternative providers (for their wellbeing support, and their education)

External staff training and qualification requirements

Factual judgements (‘What is’):

Stigma against mental health issues and seeking help

Social inequality negatively impacting access to variety of support, likelihood of poor circumstances and outcomes, and potentially response to available support

Individual circumstances of students and staff

Student preferences

Capacity of external health and social services

Legal requirements

External certification

Institutional inspectors

Boundary Critique:

Students and staff are consulted for their input which helps with bringing attention to societal issues and individual differences that can affect the implementation and effectiveness of strategies, policies and interventions.

Decision-making is enacted through hierarchical management structures in which those who hold power may not place equal value on contributions from students and teaching staff.

Leadership and board members are not representative of student populations and may not relate to their concerns, or see the importance of issues raised, but they do have insight into institutional operations and how they interact with environmental influences.

Hierarchical structures rely on accountability and transparency at higher levels to avoid abuses of power that harm ‘lower levels’.

-

[CSHq8] Expertise

Value judgements (‘What ought to be’):

Systems thinking and group workshop facilitation

Teaching and learning

Wellbeing and mental health

Institutional structures, functions, resources, roles, and capacity to enact change at various levels

The needs of stakeholders

Factual judgements (‘What is’):

Data analysis

Student support

Equity, Diversity, Inclusion, Accessibility

Project management

Administration

[CSHq7] Experts

Value judgements (‘What ought to be’):

Systems thinking experts and facilitators

Wellbeing experts

Teaching staff

Support staff

Department managers

OU leadership

Students

Advocacy groups and representatives

Ideally all stakeholders participate in making strategy that is systemically desirable

Factual judgements (‘What is’):

Data analysts

OU wellbeing professionals

Student Support

Students and staff who provide feedback

Managers and administrators ensuring project completion within institutional constraints

[CSHq9] Guarantors

Value judgements (‘What ought to be’):

Feedback from stakeholders is in support of actions taken and decisions made

External agencies evaluate and provide verifications

Changes in interventions, practices and processes align with improvements in measures of performance

Peer-reviewed research or demonstrable systemic improvements for wellbeing in academic institutions, support claims of expertise

Professionals provide certification and can prove they have relevant experience and skills

Factual judgements (‘What is’):

OU Key Performance Indicators

Leadership accountability to governing bodies

Boundary Critique:

The students and staff that are not heard, whether they reach out or not, could contribute to the bigger picture on why some people fall through the cracks.

There are structural and economic limitations that require careful balance of resource management, satisfaction of shareholders, fulfilment of legal obligations, and adherance to brand values / image. Realistically this is a difficult balance to maintain and a lot can go to the wayside when priority goes to ‘keeping the lights on’. Having spoken to EDIA lead (Lotz, 2025), budgets have not necessarily been a concern in implementing changes, so there could potentially be more of a push towards the ‘ideal’.

Quantitative and qualitative data can provide invaluable insight into efficacy, efficiency, and effectiveness. The extent that each is utilised and valued as sources for evaluation is unclear.

-

[CSHq11] Emancipation

Value judgements (‘What ought to be’):

Inclusive culture of open communication, accessible feedback systems, and ability to whistleblow without negative repercussions

Co-design of policy and strategy informed by stakeholder feedback

Student representatives have the opportunity to advocate for students' rights and representation of marginalised groups or individuals in discussions

Union representatives can negotiate for reasonable workers' rights, working hours, compensation, and appropriate support

Institutional support for communities of practice and critical social learning systems

Consideration of impact of interventions on wider communities, and health and social care services

Factual judgements (‘What is’):

EDIA department advocating for marginalised groups

OUSA, Student Voice, feedback questionnaires, consultations inclusive of student representatives

Universities UK providing guidance to institutions regarding ‘whole institution’ approach to healthy universities

UK law, Education authorities and inspection agencies enforcing institutional practices that protect wellbeing of students and staff

OU compliance with legal requirements

[CSHq10] Witnesses

Value judgements (‘What ought to be’):

Workers’ unions, support communities and representatives

Student Union, support communities and representatives

External healthcare and wellbeing organisations that may not be directly involved in stakeholder discussions, but may be affected by effectiveness of internal OU wellbeing practices

Factual judgements (‘What is’):

Staff that are overworked or have their own wellbeing overlooked and harmed by interventions they have to run to support students

Postgraduate students, or those not considered a part of priority groups for interventions

External student support organisations that have less of an opportunity to prevent poor wellbeing but have to deal with the consequences

[CSHq12] Worldviews

Value judgements (‘What ought to be’):

Systems and processes for balanced response to both quantitative and qualitative feedback in strategic negotiation

Long term research and continual monitoring on how accommodation of differing worldviews in institutional strategy impacts wellbeing

Long term evaluation and development of strategies for improving staff and student wellbeing with other institutional functions, resource management, sustainability etc.

Co-creation of meaning around what wellbeing is and how it can be supported

Co-design of wellbeing interventions, collective identification of measures of success, and design of processes for monitoring and evaluation

Accommodations / considerations for all stakeholders explicitly outlined in policy and strategy as standard

Factual judgements (‘What is’):

Inclusion of student representatives in design and evaluation of wellbeing and EDIA initiatives

Compliance with legal requirements for protection of individuals from vulnerable groups

Representation of priority groups’ needs through EDIA leadership and embedding of EDIA throughout the institution, professional practice and curricula

Boundary Critique:

The effectiveness of existing measures, such as the influence of staff and student unions on the improvement of wellbeing, is unclear.

Support for specific at-risk groups and their inclusion in development of strategy does support accommodation and normalisation of varying perspectives on what wellbeing is and what would help different people succeed in education. However, individuals that are not part of priority groups may not have the same support available when they need it.